The study of two portraits of the jurist Michele Perremuto († 1806) provides original visual perspectives on the transformations affecting the figure of the jurist between the second half of the 18th century and the early years of the 19th century, an age of transition from the context of the late Ius Commune towards the age of the codification of law.

Lo studio di due ritratti del giurista Michele Perremuto († 1806) offre originali prospettive visuali sulle trasformazioni che interessano la figura del giurista tra la seconda metà del Settecento e i primi anni dell’Ottocento, un’età di transizione dal contesto del tardo Diritto comune verso l’età della codificazione.

CONTENUTI CORRELATI: Portrait - Jurist - Lawyer - Judge - Sicily - Michele Perremuto - Ritratto - giurista - avvocato - giudice - Sicilia

1. The House of Perremuto - 2. The First Portrait of Michele Perremuto: Lawyer-Judge - 3. The Second Portrait of Michele Perremuto: The President-Scholar - Bibliography - NOTE

Museums, private collections, and dusty galleries of institutional buildings count numerous portraits of jurists among their paintings. They are often recognizable by certain elements included in the pictorial composition, or by the posture, or even by the setting; these elements are often combined. These portraits are characterised as function-portraits, expressing a peculiar sensitivity towards the representation of models of power that are embodied in the canvas, intended to convey a message to the viewer that is no longer easy to decode[1].

Two ancient works of art, an oil on canvas and a sculpture, portray a famous Sicilian jurist, who ascended to the highest ranks of magistracy in a period characterised by important changes in the field of both legal and political-institutional culture: the phenomenon of the codification of law was fast approaching, while the Kingdom of Sicily was about to conclude its historical course with its inclusion in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Our story begins in an old house that still preserves the memories of Michele Perremuto, a jurist who lived between the 18th century and the first years of the 19th century. In the ballroom of the Perremuto Palace in Caltagirone (today known as Crescimanno d’Albafiorita), there is a notable gallery of family portraits: one of them portrays him in his maturity. Perremuto’s tomb in Palermo (which Michele shares with his brother Giuseppe) depicts him in a different pose. Further elements are revealed on the psychology of the character, emblematic of the professional milieu of jurists in that period, linked to the different functions held in the time segments referable to the two portraits. Moreover, the changed social outlook towards the figure of the jurist, sensitive to the historical turning point between the 18th and 19th centuries, and to the process of codification of law that was also beginning to affect remote Sicily, are uncovered. These two works of art structure this essay, which is part of a broader study of mine on jurists’ portraits in the Modern Age.

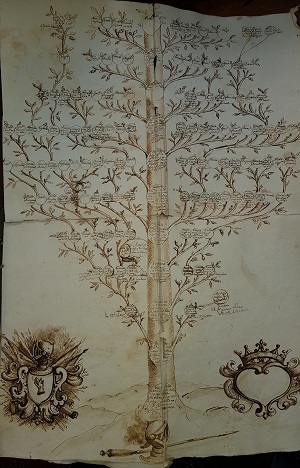

Proud Knights of Iberian origin, who had come to Sicily with the Martini dynasty at the end of the 14th century (Fig. 1), the Perremuto family approached the legal professions at the beginning of the 16th century.

They followed a model already experimented by other lineages, taking root in a state-owned city that certainly offered law graduates numerous employment and career opportunities[2], also ensured by inclusion in the Mastra nobile[3]. The family consolidated its noble status also thanks to shrewd marriages with heirs of baronial lineages or families accepted into the Order of the Knights of Malta[4]. This rise can be considered accomplished in the early 17th century, thanks to Federico’s investiture as Baron of Boschitello and his marriage to an heiress of Bonaventura Secusio, one of the most influential ecclesiastics and closest to the Spanish Crown[5]. On the strength of his kinship with the prelate, in 1624 Federico himself attempted a further step in the legal career: his wife Brigida wrote to King Philip IV in order to plead for her husband’s appointment as a Judge of the Concistoro della Sacra Regia Coscienza (one of the most important Courts of the Kingdom of Sicily). Yet, the attempt was unsuccessful[6].

Fig. 1 – The Perremuto Family Tree

Fig. 1 – The Perremuto Family Tree

Paolo Francesco Perremuto was indeed a prince among lawyers: born in 1620, he was several times a judge in Caltagirone, in whose Studium he was a Professor of Ius civile[7]. He moved to Palermo, where he practised law and was a Judge of the Corte Pretoriana. Then he ascended to the prestigious seats of the central magistracies of the Kingdom of Sicily: he was a Judge of the Regia Gran Corte (Royal Great Court) and of the Concistoro della Sacra regia Coscienza[8]. Paolo Francesco is known as the author of Conflictus iure consultorum inter sese discrepantium. This was actually an emblematic text of the period of the «ultime vittorie del Diritto comune»[9], as the title of a chapter of Adriano Cavanna’s manual says, according to which this work was «una vera giungla dottrinale in cui il Perremuto tenta con caparbio sforzo di aprirsi la strada della certezza»[10]. Yet, Ludovico Antonio Muratori’s trenchant opinion weighed down this work[11]. The conflict of doctores turned out to be a very useful tool for practical jurists, who daily faced in the courts the problems of searching for the communis opinio: it was a handbook that allowed them to quickly find jurists who had approved or contested the positions of other doctores, without getting lost in never-ending researches. In this sense, Muratori was right: it was certainly a formidable weapon in the hands of legal practitioners, but also a fundamental tool to offer a safer course in what Cavanna so colourfully depicted as a ‘doctrinal jungle’.

The family’s history unfolded during the late 17th century and throughout the 18th century along the path already marked out by their ancestors: presence in the magistracies of the Kingdom of Sicily, profitable professional activity, good matrimonial alliances, and participation in ecclesiastical offices. The eldest son of Paolo Francesco, also a doctor iuris, Federico, was Castellan of Caltagirone. A cadet, Michele sr., remained in Palermo, the capital of the Kingdom, following his father’s steps, and was engaged in the magistracies: as a Judge of the city Court, of the Court of the Concistoro, and of the Regia Gran Corte[12], he was considered one of the most famous lawyers of his time.

However, the long parable of the Perremuto family was nearing its end. On 11 March 1791, the Benedictine Paolo Francesco (born Ignazio), Archbishop of Messina, also present in the Palace hall in a portrait by Giuseppe Crestadoro (Fig. 2)[13], died of apoplexy during the celebration of mass.

Fig. 2 – Portrait of Archbishop Paolo Francesco Perremuto (Giuseppe Crestadoro,

Fig. 2 – Portrait of Archbishop Paolo Francesco Perremuto (Giuseppe Crestadoro,

end of eighteenth Century, private collection, photo by Andrea Annaloro)

Family memory recalls a mysterious anonymous message that the prelate had received a year earlier: «Perremuto statti muto / all’anno avrai il tabbuto»[14]. The curse of the silent dog, the mute ‘perro’ of the family coat of arms (the severed and bleeding head of a black dog in a gold field) (Fig. 3), actually struck the prelate a year later. According to the transmitted tradition, some poison had been poured into the chalice of the Eucharistic celebration: a story that Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa mentions in The Leopard, in a dialogue between Tancredi and Chevalley[15].

Fig. 3 – Coat of Arms of the Perremuto Family (private collection)

Fig. 3 – Coat of Arms of the Perremuto Family (private collection)

The life of Michele Perremuto Tedeschi, born in 1728, great grandson of Paolo Francesco, the author of Conflictus, is well depicted in his funeral oration: «L’ordine della nostra nascita dà quasi sempre la direzione de’ nostri destini; le armi e la toga erano le vie sulle quali poteva incamminarsi il cavaliere Perremuto. Egli scelse quest’ultima, che reputò più degna del suo carattere e de’ suoi talenti»[16]. Michele became a Judge of the Regia Gran Corte, a position he held for three years, in 1768, 1774, 1778; then he was an accusing officer at the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio (Court of the Royal Property), a position he later held at the Regia Gran Corte, in addition to that of honorary ‘Maestro razionale’ of the Real Patrimonio.

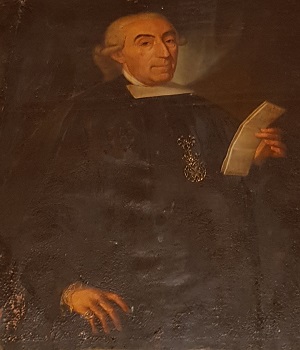

To this period of the jurist’s life belongs the first portrait[17] (Fig. 4), painted by Leonardo Guzzardi, portrait painter active in Palermo in the second half of the 18th century[18]. Michele (who appears from his physiognomy to be in his early fifties) is portrayed cloaked in a robe, the insignia of power of the jurist order, standing, in the typical pose of a lawyer preparing to plead. His right hand with a precious ring on his little finger rests on his hip; his left hand holds a legal dossier addressed to him. He wears a powdered wig on his head; a pierce, haughty glance is directed towards the observer. The only decoration, standing out against the black of the robe, is a precious Maltese Cross, an ostentatious sign of membership of the prestigious military Order[19]. This is the portrait of a proud lawyer, a jurist of the late age of the ius commune, in whom the attitude of the lawyer and that of the judge still coexist.

Fig. 4 – Portrait of Michele Perremuto (Leonardo Guzzardi, eighteenth Century,

Fig. 4 – Portrait of Michele Perremuto (Leonardo Guzzardi, eighteenth Century,

private collection, photo by Andrea Annaloro)

In the lower part of the portrait[20] there is a cartouche, which follows the outline of the Rococo frame of the over door, on which an inscription derived from that of Perremuto’s grave was painted later[21].

Later, King Ferdinand, IV of Naples and III of Sicily, called Perremuto to Naples as regent of the Suprema Giunta di Sicilia (Supreme Council of Sicily), an important office that ensured the connection between the Sicilian Crown and the Southern Kingdom. Michele was later appointed Minister of the Giunta dei Presidenti e del Consultore (Council of Presidents and Consultant), before ascending in 1787 to the coveted seat of President of the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio[22] and finally reaching the apex of the Island’s magistracy, becoming President of the Court of the Regia Gran Corte in 1805. An exemplary career, in a complex period for Sicilian jurists, marked by the sovereign’s first exile in Palermo and the start of a cautious reformism following the echoes of the French Revolution. In that time, a few great jurists kept their privileges and prerogatives intact, at the top of a forensic structure that was still imbued with the Ancien Régime[23].

This is where another appearance of Perremuto as a judge of the Regia Gran Corte takes place: he was among those who sentenced the lawyer Francesco Paolo Di Blasi (one of the protagonists of Leonardo Sciascia’s novel Il Consiglio d’Egitto[24]) to death as a State offender in 1795, at the end of a trial characterised by extraordinary procedures.

Perremuto’s life experienced major changes in the so-called ‘English years’ of Sicily. The King had moved to Palermo, fleeing from the French-occupied Naples. In the resurrected capital, the splendours of a court in exile were taking place, amid festivities and parties, under the sign of new fashions and enthralling collective rituals. The account books of the Perremuto record the careful renovation and decoration of a ‘casina’ at the Colli, a holiday resort of the Palermo aristocracy, a villa owned by the family since Paolo Francesco, the author of Conflictus[25], a summer residence for such an eminent personage, where he could worthily meet illustrious guests. The densely annotated pages tell us of the human dimension of the character. Thus, we are informed of the purchase of chocolate for the rituals of the reception; of the gentleman’s predilection for fine Havana tobacco to fill his snuff box, still following a fully 18th-century taste; finally, of his preference for Marsala wine, which the English sipped with voluptuousness at the time, since the Continental System imposed by Napoleon prevented them from obtaining Port wine.

The new times also required the elderly magistrate to take dancing lessons; he could hardly risk not appearing à la page at ball in Palermo’s restored Royal Palace. Yet, that was not enough. Perremuto also hired a French language teacher, so that he would not find himself at a disadvantage in the gallant conversations that animated Palermo’s aristocracy, between parties in the city’s sumptuous palaces and the first ice creams to taste in the vast parks of Bagheria’s villas.

As the Marquis of Villabianca recalled in his chronology of the Presidents of the Regia Gran Corte, Michele had no wife «ché mai ne (h)a voluta prendere per vacare soltanto al disimpegno de’ doveri»[26]. His trusted brother Giuseppe, also unmarried, accompanied him in his stay in Palermo[27], where the President died in 1806 at the age of 77[28].

This is where the second portrait comes into play, within a marble oval on display in Perremuto’s tomb, attributable to the sculptor Federico Siracusa from Trapani[29]. On the wall of the nave of the Capuchin Church in Palermo, a neo-classical ark, adorned with the family coat of arms, resting on a base with a commemorative inscription, holds a grey marble stele, on which is set a white marble oval, where the busts of the two brothers are sculpted. On the sides, there are two Lictor’s fasces, recalling the power of the magistrate, and two oblong, moulded slabs, symbolising the Tables of the Law (Fig. 5).

![Fig. 5 – Funeral Monument of Michele e Giuseppe Perremuto (Federico Siracusa [attr.], Palermo, Chiesa dei Cappuccini, 1807)](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/GP/GPG.2022.005.jpg) Fig. 5 – Funeral Monument of Michele e Giuseppe Perremuto

Fig. 5 – Funeral Monument of Michele e Giuseppe Perremuto

(Federico Siracusa [attr.], Palermo, Chiesa dei Cappuccini, 1807)

The last public representation handed down to posterity portrays Michele with the head covered by the wig. Yet, he no longer wears the robe, but is dressed in a tailcoat, always with the Maltese Cross pinned to the left side of his jacket. Michele is not portrayed as in the painting already analysed, but as a legal scholar: a cultured interpreter, navigating through the sources of the late ius commune, the volumes of the Jus Siculum. His absorbed glance rests on a passage indicated by the finger of his right hand, while his left holds the volume (Fig. 6).

![Fig. 6 – Detail of the Funeral Monument of Michele and Giuseppe Perremuto (Federico Siracusa [attr.], Palermo, Chiesa dei Cappuccini, 1807)](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/GP/GPG.2022.006.jpg) Fig. 6 – Detail of the Funeral Monument of Michele and Giuseppe Perremuto

Fig. 6 – Detail of the Funeral Monument of Michele and Giuseppe Perremuto

(Federico Siracusa [attr.], Palermo, Chiesa dei Cappuccini, 1807)

An expert, indeed, still eager for knowledge, eternally engaged in a tireless and never-ending search, through the pages of the open legal volumes that occupy the lower part of the depiction. A glance still fully eighteenth-century, with the watchful and devoted shadow of his brother at his side, even after death. A truly emblematic monument to a life spent in the service of the Law, as the inscription at the foot of the grave reads:

These two portraits, the lawyer-judge and the President-man of science, highlight the different souls of the jurist in the transition between the late age of the ius commune and the age of codification. The different representations document the progressive transformation of the image of the jurist. On the one hand, the lawyer of Ancient Régime, expert of the system of the ius commune, aware of the power deriving from his auctoritas and from the ability to navigate easily through the different normative and jurisprudential sources. He was the expression of a unitary context in which lawyers and judges were part of the same class and identified with the main symbol of that membership, the robe[30]. On the other hand, a jurist who was beginning to be caged within well-defined roles that would soon distinguish magistrates from professional men, severing the fertile osmosis that had characterised the Modern Age. A jurist overlooking on a rapidly changing landscape, which with the advent of codes would propose a new 19th-century anthropology of the lawyer three in one: lawyer, professor, and politician[31].

The Perremuto family soon died out, their villa decayed, until its recent demolition, a sad fate shared with other buildings destroyed by Palermo’s urban expansion. The fortunes of the Perremuto were passed on to other lineages who lived in the ancient house. Here Michele still melancholically observes the new guests from the portrait of the ‘camerone’, the ballroom, in the shadow of the severed head of the lugubrious but faithful mute dog, ‘perro muto’, silently barking on the high vaults, an icon of the family of jurists, described in these baroque verses dedicated to the work of Paolo Francesco[32]:

Beneduce, Pasquale (1996), Il corpo eloquente. Identificazione del giurista in età liberale, Bologna, il Mulino

Beneduce, Pasquale (2003), Cause in vista. Racconto e messa in scena del processo celebre, in «Giornale di Storia costituzionale», n. 6/II, pp. 333-344

Beyer, Andreas (2002), Das Porträt in der Malerei, München, Hirmer Verlag

Cappuccio, Antonio (2018), «La Toga, uguale per tutti». Potere giudiziario e professioni forensi in Sicilia nella transizione tra Antico Regime e Restaurazione (1812-1848), Bologna, il Mulino

Cavanna, Adriano (1979), Storia del diritto moderno in Europa. I. Le fonti e il pensiero giuridico, Milano, Giuffrè

Caversazzi, Ciro, Gino Fogolari, Carlo Gamba (e altri) (1911), Il ritratto italiano dal Caravaggio al Tiepolo alla mostra di Palazzo Vecchio nel 1911 sotto gli auspici del Comune di Firenze, Prefazione di U. Ojetti, Bergamo, Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche

Delorenzi, Paolo (2009), La Galleria di Minerva. Il ritratto di rappresentanza nella Venezia del Settecento, Venezia, Venezia Barocca

Di Natale, Maria Concetta (2019). Ritratti in Sicilia tra Sei e Ottocento, in Brevetti, Giulio (a cura di), La Fantasia e la storia. Studi di Storia dell’arte sul ritratto dal Medioevo al contemporaneo, Palermo, Palermo University Press, pp. 109-126

Emanuele e Gaetani di Villabianca, Francesco Maria (1754), Della Sicilia nobile, P.I, l. IV, Palermo, Stamperia de’ Santi Apostoli

Emanuele e Gaetani di Villabianca, Francesco Maria (s.d.), ms. Palermo, Biblioteca Comunale, QqE112, sez. Presidenti di Patrimonio

Fossi, Gloria (a cura di) (1996), Il Ritratto. Gli artisti, i modelli, la memoria, Firenze, Giunti

Gallo, Agostino (2004), Notizie de’ figulari degli scultori e fonditori e cisellatori siciliani ed esteri che son fioriti in Sicilia da più antichi tempi fino al 1846 raccolte con diligenza da Agostino Gallo da Palermo (Ms. XV.H.16., cc 1r-25r; Ms. XV.H.15., cc 62r-884r, trascr. e note di Angela Anselmo e Maria Carmela Zimmardi, Palermo, Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni culturali)

Gandolfi, Giulia (2007), Diritto all’immagine, diritto alla fama. Il ritratto del potere nell’epoca moderna, in «Storicamente», 3, Art. n. 16

Lo Piccolo, Francesco (1995), In rure sacra: le chiese rurali dell’Agro palermitano: dall’indagine di Antonino Mongitore ai giorni nostri, Palermo, Accademia nazionale di Scienze, Lettere e Arti

Lopes, Giovanna (a cura di) (1999), Federico Siracusa alla bottega del Marabitti nella Sicilia del XVIII secolo. Mostra storico-fotografica, Palermo, Biblioteca francescana, 17-31 luglio 1999, fotografie di Fabrizio Porcaro, Palermo, Associazione turistica e culturale Post meridiem

Mango di Casalgerardo, Antonino (1915), Nobiliario di Sicilia, II, Palermo, Reber

Manzoni, Gaspare (1806), Elogio del cavaliere d. Michele Maria Perremuto Presidente della Gran Corte, recitato nell’Accademia del buon Gusto il giorno 20 aprile 1806, Palermo, Reale Stamperia

Mazzacane, Aldo, Cristina Vano (1994), Università e professioni giuridiche in Europa nell’età liberale, Napoli, Jovene

Muratori, Ludovico Antonio (1742), Dei difetti della Giurisprudenza, Venezia, Pasquali

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (1996), Il governo dei gentiluomini. Ceti dirigenti e magistrature a Caltagirone tra medioevo ed età moderna, Roma, Il Cigno Galileo Galilei

Pace Gravina, Giacomo, Luciano Buono (a cura di) (2003), La Sicilia dei cavalieri. Le istituzioni dell’Ordine di Malta in età moderna (1530-1826), Roma, Sovrano Militare Ordine di Malta, Fondazione Donna Maria Marullo di Condojanni,

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (2013a), Per una antropologia dell’avvocato siciliano dell’Ottocento, in Migliorino, Francesco, Giacomo Pace Gravina (a cura di), Cultura e tecnica forense tra dimensione siciliana e vocazione europea, Bologna, il Mulino, pp. 15-63

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (2013b), Un diplomatico siciliano tra guerre di religione e impegno pastorale: Bonaventura Secusio, in «Rivista di Storia del Diritto italiano», 86, pp. 23-38

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (2015), Il ritratto del Patriarca. Una raffigurazione di Bonaventura Secusio nella pinacoteca dei Musei Civici di Caltagirone, in Ciccarelli, Diego, Francesco Failla (a cura di), Francescanesimo, fede e cultura nella diocesi di Caltagirone. Atti del Convegno di studio, Caltagirone, 16-18 dicembre 2011, Palermo, Officina di Studi medievali

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (2019), Giuristi e potere nella Sicilia moderna: i Perremuto, in «Historia et ius – Rivista di storia giuridica dell’età medievale e moderna», 15/2019 – paper 24

Pace Gravina, Giacomo (2022), Il ‘Secolo dei lumi’ di Leonardo Sciascia: tra Controversia liparitana e Consiglio d’Egitto, in Cappuccio, Antonio, Giacomo Pace Gravina (a cura di), Leonardo Sciascia e la Storia del diritto, Messina, Messina University Press

Pasciuta, Beatrice (2015), voce Perramuto (Perremuto) Paolo Francesco, in Birocchi, Italo, Ennio Cortese, Antonello Mattone, Marco Nicola Miletti (a cura di), Dizionario biografico dei giuristi italiani, II, Bologna, Il Mulino, p. 1546

Petit, Carlos (2013), Biblioteca, archivo, escribania. Portrait del abogado Manuel Cortina, in Migliorino, Francesco, Giacomo Pace Gravina (a cura di), Cultura e tecnica forense tra dimensione siciliana e vocazione europea, Bologna, il Mulino, pp. 87-151

Pommier, Edouard (2003), Il ritratto. Storia e Teorie dal Rinascimento all’Età dei Lumi, Torino, Einaudi

Sarullo, Luigi (1993), Dizionario degli artisti siciliani, Palermo, Novecento

Sgarbi, Vittorio (a cura di) (2005), Ritratto interiore. Da Tiziano a De Chirico, da Lotto a Pirandello, Milano, Skira

Simmel, Georg (1985), Il volto e il ritratto. Saggi sull’arte, trad. it. di L. Perucchi, Bologna, il Mulino

Taranto, Emanuele (1857), La festa del Conte in Caltagirone, Catania, Galatola

Tomasi di Lampedusa, Giuseppe (1958), Il gattopardo, Milano, Feltrinelli

Zorzi, Renzo (a cura di) (2002), Le metamorfosi del ritratto, Fondazione Giorgio Cini – Civiltà veneziana. Saggi, vol. 43, Firenze, Olschki

[1] Pace Gravina (2013a), pp. 35 e ss.; Beneduce (2003), p. 340. On the image of the jurist, see also Beneduce (1996).

[2] On this perspective, see Pace Gravina (1996).

[3] On the ample manoeuvring area offered to jurists of Caltagirone, cf. Pace Gravina (1996); see also Archivio Conte Gravina, Caltagirone [from now on ACG], Perremuto, t. 10; Taranto (1857), p. 75 nt. 56.

[4] On the presence of the Knights on the Island, cf. Pace Gravina/Buono (2003).

[5] On Bonaventura Secusio, see Pace Gravina (2013b) and (2015), pp. 127-134.

[6] ACG, Scritture momentanee della Casa Perremuto, t. 39, fol. 26 r-v; t. 10, fol. 62.

[7] On the history of the Studium, of Caltagirone cf. Pace Gravina (1996), pp. 271-272; (2004), pp. 21 ss.

[8] Detailed information on the life of Paolo Francesco and the magistracies he held is provided by his son Federico: cf. ACG, Genealogia Perremuto, «Genealogia fedele della nobilissima famiglia Perremuto nella città di Caltagirone, originaria da provincie spagnuole, ordinata da D. Federico Perremuto e Cacioppo Barone di Biscottello, Regio Castellano e Patritio Caltagironese».

[9] «The last victories of the Ius Commune».

[10] «An actual doctrinal jungle, in which Perremuto stubbornly attempts to open up the road to certainty»: Cavanna (1979), p. 259.

[11] Muratori (1742), p. 71: «siccome ancora s’è veduto dopo la metà del secolo prossimo passato arditamente mettersi a divolgar le piaghe della moderna Giurisprudenza il Baron Paolo Francesco Perremuto, legista siciliano, con raccogliere in cinque tomi un’infinità di discrepanze, e contrarietà de i Comentatori delle Leggi, de’ Consulenti, e delle decisioni stesse della Ruota romana, non che d’altri insigni tribunali: libro d’incredibil fatica e libro utile non già per introdurre la pace e la concordia in questa nobil professione, ma solamente per somministrar armi da offesa e difesa a chiunque l’esercita». The passage is quoted and used by Cavanna (1979), p. 259. On Paolo Francesco Perremuto, cf. Pace Gravina (2019), Pasciuta (2015).

[12] Mango di Casalgerardo (1915), p. 64; Emanuele e Gaetani di Villabianca (1754), p. 255. Also, cf. ACG, Genealogia Perremuto.

[13] Cf. Taranto (1857), pp. 94-95 nt. 89.

[14] «Perremuto shut up / in a year you will have a coffin».

[15] Tomasi di Lampedusa (1958), p. 117. On the death of the archbishop, see ACG, Perremuto, vol. 54, fol. 327, containing the report of d. Filippo Hernandez: «fu di repente, mentre celebrava l’incruento sagrifizio, colpito da apoplessia, che non gli diede altro tempo, se non di ricevere con esemplarità gli ultimi Sagramenti».

[16] «The order of our birth nearly always gives direction to our destinies; the Army or Judiciary were the paths on which the Knight Perremuto could set out. He chose the latter, which he deemed more worthy of his character and talents».

[17] On portraiture, within the vast bibliography, I will only mention here: Caversazzi/Fogolari/Gamba (1911); Simmel (1985); Fossi (1996); Zorzi (2002); Beyer (2002); Pommier (2003); Sgarbi (2005); Gandolfi (2007); Delorenzi (2009).

[18] About Leonardo Guzzardi († 1802), the deaf-mute painter from Sambuca, author of numerous portraits, including those of Horace Nelson, Lady Hamilton, and Filippo Lopez y Rojo, Archbishop of Palermo, see Gallo (2004), p. 237; Sarullo (1993), s.v. I thank Francesco Paolo Campione for these pointers, and the Countess Gravina for her customary kindness in publishing the Perremuto portraits.

[19] On the presence of Maltese Crosses in the portraits of Sicilian aristocrats, cf. Di Natale (2019), p. 116.

[20] The characteristics of the painting seem reminiscent of the portrait of Viceroy Giovanni Fogliani d’Aragona in the Royal Palace in Palermo, painted by a Sicilian painter probably around 1775, which presents a similar ‘celebratory’ approach. I thank Francesco Paolo Campione for the information.

[21] «D.O.M. Aeternaeque memoriae Michaelis Perremuto e patricia familia equitis / Hieros. iurisconss. qui a brevioribus subsellis ad ampliora progressus / Fisci patrocinium egit ad Neapolitanum consessum / Siciliae causarum apud Regem ad scitus indeq. regio / aerario Siciliensi per annos duodeviginti / praefectus supremi tandem sacrique Se/natus magnaeq. Curiae praeses sapientia / iustitia integritate / bene de cunctis ordi/nibus merendo id est consequutus ut / nec defuerit viventi honos nec vita fu/ncto commune civium desiderium / vixit annos LXXVII M. VII D. XXII obiit / A. 16 martii 1806».

[22] Cf. F.M. Emanuele e Gaetani di Villabianca, ms. Palermo, Biblioteca Comunale, QqE112, sez. Presidenti di Patrimonio, pp. 417-18.

[23] On this cultural context, see the considerations of Cappuccio (2018), pp. 27 e ss.

[24] On this topic, see Pace Gravina (2022).

[25] Lo Piccolo (1995), p. 264. The Villa of Perremuto family was recently demolished. I thank Claudio Gino Li Chiavi for the information kindly provided.

[26] «For he never wanted to take one in order to devote himself only to his duties».

[27] Giuseppe was general proxy of Caltagirone in Palermo: cf. ACG, Perremuto, t. 6.

[28] Cf. Manzoni (1806); Taranto (1857), pp. 93-94 nt. 86; Mango di Casalgerardo (1915), p. 64.

[29] On Federico Siracusa (Trapani, 1759-Palermo, 1837), among the leading exponents of Sicilian sculptural neoclassicism, cf. Lopes (1999); Gallo (2004), pp. 263-267. I would like to thank Claudio Gino Li Chiavi and Francesco Paolo Campione for the images of the monument. In the same Capuchin church, and again by Federico Siracusa, are the tombs of the brothers Antonio († 1802) and Onofrio Ardizzone († 1791), which present a compositional structure similar to the Perremuto Monument. The two subjects, however, still embody the model of the portrait aimed at showing the role and power of the portrayed person, while the perspective of Perremuto’s profile is certainly original.

[30] Pace Gravina (2013a); Cappuccio (2018).

[31] Mazzacane/Vano (1994), Pace Gravina (2013).

[32] Pace Gravina (2019).

[33] «You are a dumb dog / but then writing you bark / of Astrea’s laws guardian on Earth / the suit at your barking flees underground».