This paper presents the need to combine colonial photography with food history and analyse how important it was for Europeans to represent themselves in photographs when celebrating a white dining culture in Africa. It shows how self-representation was part of a visual global order, the creation of an African stereotype and how food played an integral part of (re-)enforcing whiteness amongst Europeans for whom the rejection of indigenous foods was a method of racial marking and power over the non-European. Also, racial stereotyping is linked to rulemaking, a pre-step to colonial laws, in a colonial context thereby linking it to elitist seeing customs. The case study approach is based on the Mecklenburg-Collection. Its visual ego-documents are discussed according to whiteness and postcolonial studies approaches, the Panofsky image analysis method and supported by diaries and travelogues.

L’articolo dimostra la rilevanza di combinare la fotografia coloniale con la storia del cibo e analizza l’importanza per gli europei di vedersi rappresentati in immagini fotografiche mentre celebravano la cultura da pranzo ‘bianca’ in Africa. Il contributo spiega come la rappresentazione del sè europeo fosse parte di un ordine globale visivo e di creazione di uno stereotipo africano. Il cibo era parte integrale dell’affermazione della bianchezza fra gli europei, per i quali il rifiuto del cibo indigeno era un metodo di demarcazione razziale e di esercizio del potere sui non-europei. La stereotipizzazione razziale svolgeva una funzione normativa – un passaggio preliminare all’introduzione formale di leggi coloniali – in un contesto coloniale legato a costumi visivi elitari. Il caso di studio presentato nel contributo si basa sulla collezione Mecklenburg. Gli ego-documenti visivi sono indagati attraverso la lente degli studi postcoloniali e sulla bianchezza, utilizzando il metodo di analisi dell’immagine Panofsky, supportato da diari personali e di viaggio.

CONTENUTI CORRELATI: Visual History - Food History - Photography - Postcolonial Studies - German Colonialism - fotografia - storia per immagini - studi postcoloniali - storia del cibo - colonialismo tedesco

«Man, it has been said is a dining animal.

Creatures of the inferior races eat and drink;

man only dines. It has also been said that

he is a cooking animal;

but some races eat food without cooking it»

I. Beeton, The Book of Household Management,

London, S.O., 1861

1. Introduction - 2. The Mecklenburg-Expedition - - 3. Mission Civilisatrice, Dark vs Light and Visual Ego-document Analysis - 4. The Five Senses and Rulemaking in Relation to Whiteness - 5. Conclusion - Bibliography - NOTE

How important was it for European imperialists to represent themselves in photographs celebrating a white food and dining culture whilst in Africa? And how can this (re)presentation be linked to the creation of a visual global order? This article will argue two main points: Firstly, that food played an integral part of (re-)enforcing whiteness amongst Europeans (imperialists) who traversed sub-Saharan Western Africa and how it was captured in photographs. Secondly, that the rejection of most local indigenous foods was more than a mere matter of culinary likes or dislikes. Instead, the inclusion or rejection of certain foods, dishes, or drinks shall be seen as both a method of racial marking and a statement of imperial power over the non-European, thereby recreating on a cultural level the realities of an imperial global order (see for instance Fig. 1). An additional avenue taken is the aim to link racial stereotyping with cultural influences on the creation of rules or rulemaking (here seen as a pre-step to colonial laws) in a colonial context thereby also linking them to a notion of elitist seeing customs.

European photographic styles and imageries of sub-Saharan Africa as created during late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century High Imperialism, have shown to influence the depiction of Africa until this day. Popular depictions of Africa in twenty-first-century Europe and North America (the Global North) are often still based on a colonial understanding of the African continent and its visualisation from 150 years ago. Colonial photography is thus to be seen as a historical and cultural genre, especially when linked to issues like the colonial Other, othering, and the colonial subaltern[1].

More often than not, artificially created moments of culinary separation survived visually as physical sources and cultural influences for three reasons: being photographed, the glass plate negatives being shipped to Europe, and ultimately being kept safe in (museum/university/private) archives for decades to come. Often only generations later would these negatives be accessed in their current shape as ego-documents[2]. My claim is that food and visual history in combination with whiteness studies offer a marginalised but vital angle on the visual representation of colonial lives. Combined they highlight the intimate yet separate spheres of non-white and white in Africa. On one hand, colonisers and colonised shared numerous intimate spaces, but, on the other hand, white imperial identities were nurtured by artificially separating themselves from the colonised – especially so during meal times.

As a case study, this article applies colonial visual ego-documents to analyse matters of whiteness within a German and sub-Saharan context to portray the lengths to which white imperialists were willing to go to maintain their supposed whiteness. Additionally, an idea will be presented that allows for a connection between cultural elitism and rulemaking (thereby also linking this paper to the debates on the ‘civilising mission’).

Delving into interplays between personal perceptions uncovered in visual documents, and the increase of modern political demands in combination with new social relations, helps comprehend the development and transformation of colonial photography and its link to imperial identities and imperial scientific goals. Fittingly, this article focuses on the lives of people who were more or less ‘typical’ for their time and who were neither policy shapers or directly influencing high colonial politics. This is not to say that there was such a thing as a ‘typical colonial’. People were and are shaped by their times, places and social orders even memories they grew up in (as established by Maurice Halbwachs and later works by Aleida Assmann)[3]. And yet, despite social influences and political regimes, the people in question here enjoyed a degree of maintaining their individual agencies by making their own choices even, or especially, within strict regimes.

So far, case studies linking whiteness with empires and food have mostly looked at former British colonies like South Africa and Australia, but during the past decade whiteness studies in a non-Anglophone context have gained a larger audience amongst colonial, visual, food and legal historians[4]. This research adds to this development by focussing on eight of the nine German travellers who were members of the ‘Mecklenburg-Expedition’ – it received its name from its leader the Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg (hereinafter the Duke) – and ventured through Belgian, French, German, and Spanish colonies in Western Africa[5]. The here discussed sources will help provide a more refined understanding of imperial realities as they were practised by European colonisers in West Africa and how they were illustrated to a broader public in the global north and the latter’s influential role on creating modern history’s global order(s) not just from an economic or political angle but especially from a cultural one.

The depiction of food practices is thus intrinsically tied to research on colonising identities and the inclusion of German colonial photography strengthens the field of visual history within the mix of post-colonial approaches. The here discussed producers of said visual ego-documents not only lived at a time when new gender roles were created and pursued, but they had to react to multiple foreign challenges, and re-interpret their lives as imperial ethnologists and explorers in sub-Saharan Western Africa[6]. Further avenues taken are so-called (post)colonial eyes and the colonial gaze[7] and how those two points supported the creation of global orders from a visual culture angle. Amongst others, the works by Elizabeth Kaplan, Susan Sontag, John Berger, Jacques Presser and Jürgen Panofsky will be applied to analyse the photographic sources as well as their influential roles in the creation of long-term and multigenerational ‘seeing patterns’[8]. To support the analysis of visual ego-documents, diaries and the two-tome publication that resulted from the Mecklenburg-Expedition are included.

The next pages will briefly introduce the case study followed by the historical development of whiteness concepts and the use of ego-documents as primary sources.

Point of departure is a collection of around 4500 colonial photographs taken during an exploratory expedition to select Western-African colonies in 1910/11. Previously, in 1907/8, the Duke had already undertaken a comparable expedition to Eastern central Africa. Given the first tour’s successes from a scientific angle in particular, the Duke and numerous of his (financial) supporters concluded that a follow-up expedition was recommendable to continue the search for more central-African flora and fauna, ethnologically interesting objects, travel unmapped territories and make new acquaintances or allies[9]. The Mecklenburg-Expedition started in Hamburg, Germany, and led through the Belgian Congo (today: Democratic Republic of Congo), Cameroon, Congo-Brazzaville (today: Congo Republic), the Chad-Lake area, Fernando Póo (today: Bioko), and parts of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (today: South Sudan). In addition, the exploratory team consisted of eight further German men. The Duke’s companions were a mixed group of military and civilian men with differing professions and social backgrounds. There was the Duke’s year-long friend and travel companion Captain Walter von Wiese und Kaiserswaldau[10]. The other participants were Dr phil. nat. Hermann Schubotz, zoologist[11], Sergeant Otto Röder, member of the Cameroonian German Imperial Troops[12], the Duke’s butler Mr Schmidt[13], Ernst M. Heims, artist[14], Prof Dr med Karl Albert Haberer, medical doctor and specialist on tropical diseases[15], Dr Arnold Schultze, former Lieutenant from the German Imperial Troops[16] and finally Dr Gottfried Wilhelm Johannes Mildbraed, botanist specialised in spermatophytes, mosses and ferns[17].

During their travels, the nine participants of the Mecklenburg-Expedition[18] relied on their inherent power position to enhance their whiteness: they politicised the foods they ate by practicing a supposedly more ‘civilised’ dining culture and were photographed or photographed their team mates whilst doing so. This behaviour and the wish to later publish or present their pictures during public talks to broader European audiences reminds of today’s popular habit to photograph dishes (or eating and drinking generally) and post them on Instagram (and other social media outlets like Facebook and Twitter). Upon the group’s return to Hamburg the Duke edited a two-tome travelogue of the expedition with most of the team members contributing to it in writing or by means of photographs and drawings. Overall, 222 images were chosen for tome 1 of which 146 were photographs from the various team members, 72 of Heims’ sketches and aquarelle paintings and four pictures by a G.R. Morbig[19]. In tome 2 a total of 248 were selected and published – 171 photographs, 63 creations by Heims and 14 sketches from Schultze[20]. Given the vast amount of pictures taken during this expedition and despite hundreds of them never making it safely back to Germany, a great number of dining scenes were photographed and also commented on in the publications as well as the diaries.

Food played an integral part in (re-)enforcing whiteness amongst European men and women in Central Africa[21]. Imperialists like the Mecklenburg-Expedition members enhanced their alleged ‘racial superiority’ by politicising the foods they ate, the drinks they drank and how they celebrated both. The purpose of such a celebration of European dining culture went beyond the wish to create a home-like atmosphere in Africa. Rather, it was to distinguish between them and the African Other, and to give a glimpse of imperial realities as they were lived and recorded by German colonisers in situ[22].

The analytical timeframe starts with the Mecklenburg-Expedition team arriving in Conakry (Guinea) by ship from Hamburg on 27 July 1910 until returning to Germany at different dates in the summer of 1911. The visual source base consists of photographs that reflect the perspective of eight out of the nine individuals[23] who ultimately brought with them German customs as well as ethnological and other scientific measures on their trip[24]. Upon arrival, the group immediately commenced with taking pictures. Generally, the procedure was to take photographs, catalogue them and organise their transport to Hamburg. As was common then, glass plate negatives of 9x12 cm size were used and the photographs were made by using a contemporary reflex camera[25]. In some cases, the Duke, for instance, even developed photographs whilst in Africa[26].

The here presented visual sources are seen as mirror images of how the African Other was perceived through the German colonial gaze by means of emission or submission within German dining photographs. The goal is to take a more thorough look into stories of German explorers to produce a more insightful comprehension of how these colonisers’ attitudes might have changed (or not) over time as to how their whiteness was influenced by African experiences. Contemporary Western Europe saw the construction of what was considered white; however, it is not always clear whether this construction was intended or if it was a coincidental by-product of having previously determined what was non-white. If whiteness was considered the norm, were non-whites seen as aberrations from it? If latter was the case, how did it affect the visual creation of memories or experiences by travellers who left Germany for a distinctively non-white part of the world? And how did the taken images influence audiences in Germany and other parts of the Global North in their understanding of the mission civilisatrice and linked to that the connections between colonial rulemaking and racist world views that enabled racial hierarchies?

Around 1900 thousands of Europeans experienced an era of new ideas on race becoming culturally accepted due to their (pseudo-)scientific backing and as useful tools for penetrating Central-African territories. Colonising for the sake of generating profits was increasingly frowned upon[27]. A humanitarian reason was needed. And the mission civilisatrice approach was the perfect tool. As a result, the official reasons for colonising sub-Saharan Africa were to abolish slave trade, ‘civilise’ Africans (of which creating Western legal structures was a part), and minimise – if not eliminate – Muslim power structures there. The unofficial motive, however, was to ensure European political balance by detouring via the African continent, since former had come to suffer due to the Belgian King Leopold II’s meddling in the colonial power game. In order to publicly declare war on slave trade and slavery, yet also use cheap if not forced labour in most African colonies to increase profits of mostly European-held companies, both the imperial regimes as much as their representatives and participants needed a moral justification.

Deliberately or not, the creation of races generated an understanding of ‘white vs. black’ or ‘light vs. dark’. Social distinctions used to be based more on social class, but the nineteenth-century strengthening of the middle-class and with it the slow fall of nobility caused a reconfiguration of previous social models[28]. The old models were replaced by a notion of ‘enlightened vs. backward’; ‘modern vs. underdeveloped’; ‘Christian vs. heathen’. In a colonial context, social class was replaced by race. And with the creation of whiteness came the conviction of ‘white = modern’ and ‘non-white = backward’. Colonised dark peoples were thus considered to be in need of development and Western aid. This development inadvertently brought with it a racial aspect to colonisation which had not been there with such weight in previous centuries[29].

What is most concerning then, is how these ‘modern’ Europeans, who were raised with Christian beliefs of charity and love thy neighbour, who lived post-French Revolution ideas of equality and the right to ascend on a social class ladder, dealt with colonial situations that were racist and largely did not correspond with contemporary social developments in Europe. Did the colonial agents whose ego-pictures are analysed, develop or experience behavioural patterns of accommodation to racist colonial regimes that were in truth opposed to political and social beliefs in the respective home lands? The answer is yes, even if not permanently.

According to Mary Fulbrook, «it is important to distinguish between the ‘inner self’, the ‘monitoring eye’, and outer behaviour patterns, yet it is extraordinarily difficult for historians to gain access to the former»[30]. Even with useful written and visual sources, it is obvious that the manner of how an individual thinks, self-reflects and portrays his or her own deeds at any time, is already a historical product. No historical agent is independent from historical and social settings[31]. Even intimate scribbles in a diary are influenced by aspirations, discourses, and characteristics of the particular reported event and its settings; be that in terms of resistance, discomfort, internalisation, unconscious acceptance, or partial reaction against a matter[32]. All of these aspects/reactions/thoughts that a historical agent photographed were influenced by cultural codes and moral convictions. Human protagonists believe themselves to be individual actors, unique per se, yet they behave in accordance to a role created within or against the terms of their times. On top of that, individuals who witnessed major historical transitions are often aware themselves of their changing historical ‘self’. They are aware of which commonalities they share with their contemporaries and in which spheres of thinking, acting, and feeling they differ from each other. Every one of the colonial agents in my research had their own individual ‘social self’[33] which was shaped by and depended on the society they were raised and lived in, heedless of divergent personalities or talents. On top of that, their inner selves were also ‘acting selves’[34] – they could choose how to live their lives by making choices in good and less good times. This article is interested in the manner of how colonisers portrayed such choices in their photographs in respect to food and race – whiteness to be more precise, and how these instances can be linked to stereotyping and rule-making.

Therefore, the goal is to discover whether there were any connections between the concept of being white and how it influenced experiences on-site related to food culture and how the creation of new identities also governed the African other. The evidence so far supports Catherine Hall’s arguments about how creating colonies coincided with «the making of new subjects, colonizer and colonized» and that any form of governing stability within an empire depended heavily on «the construction of a culture and the constitution of new identities, new men and women who in a variety of ways would live with and through colonialism, as well as engaging in conflict with it»[35]. Therefore, I partly disagree with Edward Said’s or Frantz Fanon’s theories that colonialism was a one-way route directed from above by prejudiced Westerners and without major cultural or moral influences on the coloniser[36].

Contrary to my previous research and work with ego-documents where I applied photographs to combine whiteness studies with visual history to analyse the creation of identities and experiences of feeling in-between European and African cultures[37], this paper focusses on the differentiation and separation between colonisers and their local guides or go-betweens rather than white colonials adapting to the local ways entirely[38]. For the purpose of this article, it is more appropriate to comprehend that local food knowledge was most appreciated by white colonials when it facilitated hunting big game and prevent starvation but less so when concerned with dining cultures.

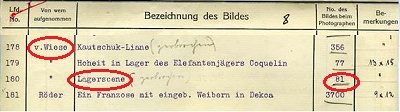

The exemplary images from the Mecklenburg collection presented and discussed in this paper have been selected based on the topic displayed in them, i.e. dining culture, the chronologic order according to the MARKK’s inventory list (e.g. laufende Nummer, see Fig. 3) and because they were taken by different members of the expedition group. Especially the last point is useful to show how the various photographers applied value to the dining culture aspect despite often taking different travel routes and being separated from each other. The following sample shows to which lengths the expedition members went to to enjoy white dining culture in sub-Saharan Africa.

I chose to begin the source presentation and discussion with a rarer example in the Mecklenburg Collection. Rare because white and non-white sit next to each other at eye level, and yet there is proof of how living a white dining culture in Africa also entailed forcing it upon colonised subjects. In the following the Panofsky picture analysis is applied. When doing so an image is analysed in three consecutive steps: i) primary subject matter, ii) iconography, iii) iconology[39]. Level (i) requires a simple description of what is visible in an image (e.g.: How many people are there?). The iconographic approach then adds a viewer’s cultural knowledge into the image’s interpretation (e.g.: How a Western person views and understands a colonial image) which is then followed by the iconological analysis that views the image not in its singularity but instead places it in a broader historical, cultural and technological setting (e.g.: Why did the photographer choose this setting and what does it mean?).

The first selected visual source, Fig. 1, is titled: Röder, Heims and Sultan Sanda.

![Fig. 1 – 2016.13:1127_Röder_Heims-Röder und Sultan Sanda[40]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.001.jpg) Fig. 1 – 2016.13:1127_Röder_Heims-Röder und Sultan Sanda[40]

Fig. 1 – 2016.13:1127_Röder_Heims-Röder und Sultan Sanda[40]

One sees five non-white men and two white men. Three men sitting and four men standing. In the front there is a table with cups and a pot and in the back-ground one sees edifices, some shrubbery and trees. Even though a non-white African dignitary was positioned centre-stage in a photograph his white companions still manage to show a certain degree of racialised disrespect. The four men in the back of the picture are (from left to right): a boy, two servants of the Sultan (in light clothes) and a higher ranking official (in dark clothes). The below image shows the Afro-Arabic subject Sultan Chefu Sanda of Dikoa, Röder (on the right) and Heims (on the left) with the latter two sitting next to the Sultan and in front of his staff. Sultan Sanda was in charge of the Dikoa Station (Deutsch Bornu) in German controlled Cameroon and bordering on the Chad Lake region. As such he was part of the German Empire as a local lord and supporter of German troops’ needs[41]. What stands out in the above image are two points: the European-style set table and the German men’s body language. The latter can be interpreted as borderline rude due to their bodies’ relaxed positioning despite being in the presence of a local dignitary. The Sultan, however, is sitting up straight and with a seemingly proud aura. Without applying a colonial gaze and the inherent power position that allowed Röder and Heims to behave as seen in the picture, those two men would have stood on a lower strung of the social ladder than the Sultan and would not have behaved in such a manner. But in a colonial setting, white skin colour triumphed over non-white titles. Heims’ writings on his encounter with Sultan Sanda support the above claims and explain his posture in the photograph. About his first encounter with the Sultan he wrote:

Shortly after, on the next page in the book, Heims states that

Thus, no matter Sultan Sanda’s comparative higher social standing and higher wealth, the two Germans see him as an inferior to themselves as we can judge from the photograph and the writings in the book chapter. Differing from the above, the following visuals will show the Mecklenburg-Expedition members enjoying themselves at set tables whilst eating and drinking when in (each other’s) company.

An aspect I wish to present now connects cultural whiteness with the five senses and relates back to medieval times where «men were generally associated with the mind and soul and women with the body and senses»[44]. A similar link was made between white people being associated with mind and soul and non-whites with the body and the senses. After all, the modern (wo)man was enlightened, civilised, and technologically advanced; i.e. (s)he was associated with products of the mind rather than with those of natural, physical, or emotional origins. Since the antiquities the so-called lower senses touch, smell, and taste were at first linked to the supposedly weaker sex, women, but throughout human history these associations altered and women were often exchanged with members of initially non-nobles and later with the lower classes. Here, the white lower classes gave way to non-whites of any couleur.

During the nineteenth century the sense of seeing became more valued in European (incl. North American) culture than the sense of touch. Sight was linked to being literate and analytical while the sense of feeling was related to illiteracy, emotions, and irrational behaviour. Nineteenth-century historical writing went as far as to create a sensory scale of races which proclaimed that the ‘civilized’ European ‘eye-man’, who focused on the visual world, was positioned at the top and the African «skin-man, who used touch as his primary sensory modality, at the bottom»[45]. Generally, it can be stated that «[…] racism drove nineteenth-century imperialism and colonialism which, in turn, drove scientists of the time to discover physical reasons that would help to account for the alleged inferiority of subject peoples […]»[46].

Linked to the ranking of the senses and European (or Western) dining culture is the expectation that after centuries of royal and noble kitchens creating luxurious dishes, sophisticated European eaters had developed a taste for recipes that were not only exquisite in tastes but also attractive to the eye. How Western consumers evaluated middle- and upper-class meals during the late nineteenth century had become increasingly linked to the meals’ visuality. A consumer’s approval depended strongly on the meal’s presentation and the artistry that came with it.

In Fig. 2 the viewer sees a group of four men sitting at a set table surrounded by trees, bushes and fallen leaves on the ground. All four men wear hats and suits. The table and chairs are foldable models and easy to transport. Visible behind the men and the table are a few tents. Slightly set apart from the table on the left is a foldable sundeck chair and on the opposite side on the right there is a dog sitting with his back to the camera. Atop the white table cloth are cups, a soda dispenser, plates and coffee or tea pots.

![Fig. 2 – 2016.13:205_Wiese_Lagerscene[47]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.002.jpg) Fig. 2 – 2016.13:205_Wiese_Lagerscene[47]

Fig. 2 – 2016.13:205_Wiese_Lagerscene[47]

A Western viewer of this image sees a group of white colonisers in a forest setting with the two men in white most likely being members of the military based on their white uniforms for the tropics and the other two men are civilians since wearing normal suits. Based on the set table and the men’s clothes a European viewer would also assume that the group consists of colonisers or travellers in non-European areas and that they enjoy certain dining culture traditions. This analysis also involves the men’s social background as being of (upper) middle or upper class. The third step includes the technological means that allowed for the image to be made, the fact that modern photography was used as a scientific tool[48] and with that the link to the MARKK’s inhouse inventory list (see Fig. 3) which tells us that the scene was photographed by von Wiese zu Kaiserswaldau, titled Lagerscene and received the MARKK’s inventory list number 180 (replacing von Wiese zu Kaiserswaldau’s internal number 81)[49]. Given the image’s age, it was part of modern colonising techniques as much as steam boats and machine guns were. Since the early twentieth century, photographing had become an inherent part of scientific endeavours in the colonies. Without a reflex camera, and sometimes even a camera for moving objects as the kinematograph that the Duke also used, colonial scientific expeditions were not seen to be sufficiently scientific[50].

Fig. 3 – MARKK inventory list of Mecklenburg Collection photographic objects

Fig. 3 – MARKK inventory list of Mecklenburg Collection photographic objects

The next pictures are more of the same and thus fitting examples for recurring shared meals at set tables which the men of the Mecklenburg-Expedition enjoyed so much. Whenever the location and weather permitted it the Duke, Haberer, Heims and other guests had their foods prepared and brought by servants. Of course, the expedition members did not always have access to a large variety of ingredients let alone a terrace. The two next images portray a special occasion. They could celebrate a meal held in honour of the German Emperor Wilhelm II’s birthday on 27 January 1911 in Kusseri[51]. Oberleutnant von Raben, Resident of Kusseri, had also invited «all of the more powerful Sultans with a following of up to 20.000 people»[52] who were all German colonial subjects to the German emperor’s birthday celebrations. And yet, despite the large number of indigenous subjects present, not even their dignitaries were invited to the luncheon seen below. These two photographs are similar yet different. The first version of the image according to the inventory list’s chronology is slightly askew and you can see two non-white servants in the background. The second version of the same social situation has the same title yet a different series number and it is without the servants. The picture’s title Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburstag translates into His Highness as a guest of the local resident – Celebration of the Emperor’s birthday.

![Fig. 4 – 2016.13:487_Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburtstag[53]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.004.jpg) Fig. 4 – 2016.13:487_Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburtstag[53]

Fig. 4 – 2016.13:487_Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburtstag[53]

![Fig. 5 – 2016.13:488_Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburtstag[54]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.005.jpg)

Fig. 5 – 2016.13:488_Hoheit als Gast des Residenten – Feier des Kaisers Geburtstag[54]

Returning to Panofsky’s method and Fig. 5, the viewer sees a group of seven men in light clothes, light shoes and dark ties sitting on chairs at a table covered by a light cloth. The scene is situated in front of a building with white walls. In the background and next to the table there are three window frames with shutters and an open door. The visible roof construction is panelled with coconut-thread carpets. On the table one can see flat champagne glasses as well as water and wine glasses and soda bottles. There is a dark medium sized glass bottle which might be a beer bottle and metal or silver cups are also visible.

Based on information from the diary and book, this particular event took place at the Station of Kusseri’s main building and is likely to have been after the meal. According to the Duke, «the Resident’s house has an airy veranda and, like the soldiers’ dwellings as well, is built of stone and whitewashed»[55]. The photographer of both pictures is listed as being Dr Haberer. The Duke is one of three men wearing hats (he is wearing one resembling a panama hat, third from right). Some men are wearing military uniforms (see shoulder pads) and others are dressed as civilians. Especially the colonial gaze plays a vital role here by showing a hierarchical view of the world based on a hegemonic order of representation built up on colonial cultural symbols and the presented self-perception[56]. White power is made visible by portraying the maintenance and legitimisation of colonial power that – as seen here – included the dehumanisation of colonised individuals and the spatial separation of white and non-white, us vs. them, ‘civilised’ vs. ‘savage’. Another symbol of western dining culture are the drinking cups on the table. Since silver cups were popular amongst the higher echelons to drink beer from, it is possible that the pictured cups were made of sterling silver. Furthermore, the availability of champagne glasses suggests just that indeed champagne was available in the middle of central Africa.

Ultimately, the above explorations fit into the imagery of a cultural umbrella that is designed to justify and replicate a highly racial and racist cultural hierarchy in modern colonial history. The twentieth century especially saw a rapid yet with each other interwoven rise and fall of various global orders. Be they linked to imperialism, fascism, democracy, different economic models, or political realities like the Cold War or post-colonialism[57]. What all of these forms of governance around the globe had and have in common are their dependence on the Global North’s mostly economic and political interests and international power plays. This paper, however, highlights a part of the Global North’s cultural power in capturing world views visually rather than limiting the analysis of a global order on economic and political issues.

Stereotypes of the African other created around 1900 by means of then modern photographic tools (including the conviction that photography was neutral and purely scientific) have manifested themselves globally and are only now in the 2000s visibly and resourcefully being questioned by activists, education curricula and other cultural institutional paths. As such, the argument is here supported that colonial visuality in connection with modern photography and seeing traditions à la Susan Sontag[58] are also responsible for the implementation and maintenance of race-based rulemaking created to keep certain societies and cultures based on skin colours separated from each other both visually and spatially.

Therefore, creating a visual colonial other was, as I argue, deeply connected to a colonising nation’s attempts to not merely make the imperial project a national goal but also to systematically construct an African other to justify the subjugation of other peoples. Enabling a narrative that put different skin colours ‘into their place’ visually was thus one part of the grander puzzle called colonialism[59]. On the formal stage, laws were introduced but before that, on the informal stage, cultural norms that would influence rulemaking had travelled from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa. The latter including visual seeing traditions both in terms of aesthetic views of the world as much as how the world is to be ordered racially. European dining cultures also entailed strict rules of where to sit, when to eat what, who is served first and which cutlery to use when. Dining culture too comes with a set of rules that represent social hierarchies similar to colonial laws.

For the sake of scope, I abstained from applying the first two steps of Panofsky’s method and instead jumped right into the third part of image analysis. Whilst there are minor differences between the respective surroundings – at a camp site, on a terrace or in front of a house – the created atmosphere in the images tends to be of a similar nature and representative for what is received as a typical colonial dining imagery. What stands out are the almost identical table settings, the light-coloured tablecloths, the beer and wine bottles, the soda water bottles, the porcelain and tin cups, the glasses, the tea or coffee pots, and also some cutlery and plates. There is a certain manner to be witnessed in the pictures that supports a worldview which thrives off and is based on how a white person can exert control over non-whites by means of creating a dehumanising narrative of non-white peoples and territories thereby justifying any kind of separation – especially by creating separate spaces in mundane everyday situations – between the colonisers and the African Other. Compared to the importance given to photographing eating situations by the Mecklenburg team members, the same can be said for the Duke’s diary entries. Spread out over 230 pages meal-related topics were documented – sometimes in more sometimes in less detail – a total of 76 times with breakfast being the most often type of meal mentioned[60].

![Fig. 6 – 2016.13:1226_Mecklenburg_Hoheit Prof. Haberer und Heims beim Frühstück[61]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.006.jpg) Fig. 6 – 2016.13:1226_Mecklenburg_Hoheit Prof. Haberer und Heims beim Frühstück[61]

Fig. 6 – 2016.13:1226_Mecklenburg_Hoheit Prof. Haberer und Heims beim Frühstück[61]

![Fig. 7 – 2016.13:1637_Mildbraed_An der Frühstückstafel in Molundu[62]](http://images.lawart.it/f/Fascicolo3/DN/DN.2022.007.jpg)

Fig. 7 – 2016.13:1637_Mildbraed_An der Frühstückstafel in Molundu[62]

Dining and drinking culture were not left behind in Europe but exported to Africa where they maintained their social functions in the humid and tropical territories as the sources linked to the Mecklenburg-Expedition show (as well as other colonial travels from the same era). Next to the two-tome travelogue, there are also two diaries by the Duke and one by his friend Captain von Wiese zu Kaiserswaldau in which they wrote about their African experiences[63]. Most of the time their diary entries relate to big game hunting and the burdensome nature of traveling through the West-African wilderness, however, whenever social gatherings were connected to food or the provisioning of food the diary entries become more detailed. Compared to other topics which the two men dotted down, food was one of the four most prominent and recurring themes[64]. This is to show that celebrating the intake of food and drink as a social activity was considered vital for their identity; both in terms of self-perception and how they wished to be perceived by their peers. Keeping in mind the technological photographic necessities during a one-year expedition (e.g. equipment’s maintenance, availability and ongoing supply of materials like glass plate negatives, and lastly organising the positives’ safe transport back to Hamburg), the expedition members did not simply photograph anything and everything. Images were carefully selected and when so desired staged. Therefore, the Mecklenburg collection objects are to be seen and examined by keeping in mind that every image and scenery was a deliberate choice by the photographer.

Displaying a knowledgeable high degree of table culture was as important to the Duke as it was to his team. Traditionally there was (and is) often a culturally produced correlation between hosting guests and women in general. But, as can be seen in these photographs, the unavailability of women did not diminish the white men’s wish for a Western dining experience. In fact, despite being within a mostly mono-gendered setting during these particular expedition circumstances, it did not minimise the importance, consumption, and decoration of food as displayed in these men’s photographs. The wish for an appropriate dining culture whilst abroad was not limited to someone’s gender. Neither was it limited to a person’s social class as is visible with this particular group which consisted of men of varying social backgrounds and ages. Instead, I argue, that the desire or need to have a European-style cultural life during an exploratory and scientific expedition was directly linked to their whiteness and to the preservation of white culture if not even white supremacy whilst being in the colonies. Examples that support the claim are amongst the small sample selection of images.

The creation of the African other was not a coincidental by-product of colonialism but happened on various levels of colonising and often so as part of a larger strategy of governance. Be it within the ethnographic and anthropological sciences of the time, in geographic or medical studies, or coming from within cultural habits themselves. Just like the photographic camera being viewed as a scientific tool so was its use in making possible rules and a legal order that was racially discriminatory. To this purpose, the previous pages have shown photographic examples of how dining experiences were used as a means to distance oneself from the African/non-white ‘Other’ as well as how othering was used to strengthen the coloniser’s own white identity inside a globally encompassing colonial order. This notion can also be applied to the idea that colonial domination itself was only possible because the colonial order was inherently racist and elitist[65] and linked to this so were rulemaking procedures and legal orders. Ultimately, a racial legal order was the result that both enhanced the governing white identity and created racist hierarchies[66].

The visual ego-documents were analysed to write history from the inside, to gather an additional understanding of how colonial characters and new identities were shaped within imperial regimes, and to show that postcolonial ideas based on Edward Said and Frantz Fanon cannot be applied to white colonials as a norm with regards to German imperial history. What this paper has done was thus also to show the necessity of analysing primary sources and related narratives that are not related to the dominating colonial histories such as the British and the French. But instead including the German narrative, for instance, as well to the global colonising project of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. At the same time, there was also no intention to white-wash former colonisers, the regimes that employed them nor their deeds.

Overall, this article argues for the vital role that the intake of food and the manner in which it was prepared, consumed, and photographed had an effect on the maintenance and shaping of identities. In a colonial context eating and drinking was used to present one’s white identity within a non-white atmosphere. At a time when photography and ethnology (science) went hand in hand with each other and truth was deemed to be an inherent component of photographic images, imperial identities could be made eternal by means of photographing identity-shaping moments. High Imperialism brought with it technological advances as much as pseudo-scientific findings that used the mission civilisatrice to justify the colonisation of non-white cultures in modern history. Whilst in Europe the bourgeoisie was on its way up the social ladder and feminist groups were slowly making their way in an increasingly meritocratic society, the colonial African ‘Other’ was minimised to his or her senses. The European eye-man was in control.

Due to modern technology such as photography, these sentiments were eternalised for future use and reproduction. Moreover, they also influenced the creation and establishment of rules if not colonial laws per se by perpetuating racist notions of superiority and inferiority in both the periphery and the metropole. Racially influenced ideas of cultural hierarchies based on racial differences, enabled not just the othering of African peoples but also the design, writing, and passing of racist (legal) rules made to control different ‘civilisationary’ groups in the colonies. This paper aimed to connect the visualisation of the African Other with a cultural global order and how the latter influences contemporary cultural debates well into the 2020s.

While the ‘breaking of bread’ is usually understood as a metaphor for a group of people coming together in a peaceful way, the available images from the Mecklenburg Collection often tell a different story. They present a narrative of selected acceptance based not on relation, meritocracy, or proximity. Instead, the tale here is one of selection, exclusion, and othering. It is a narrative of inclusion or exclusion based on race and thus represents yet another field of (cultural) rules that travelled from Europe to Africa. Food was used not merely for filling your stomach but very dominantly to show who you were, what you represented, and who you deemed fit to enter your circle of equals. Above all, as a token of ‘white civilisation’, food culture was a marker of the overarching idea that «Europeanness was […] a privilege that needed protecting»[67] and was thus not all inclusive.

Ansprenger, Franz (2007), Geschichte Afrikas, Munich, C.H. Beck

Ardener, Shirley (2002), Swedish Ventures in Cameroon 1883-1923. The Memoir of Knut Knutson, New York, Berghahn

Axelson, Sigbert (1970), Culture Confrontation in the Lower Congo: From the Old Congo Kingdom to the Congo Independent State with Special Reference to the Swedish Missionaries in the 1880’s and 1890’s, Falköping, Gummeson

Beeton, Isabella (1861), The Book of Household Management, London, S.O.

Belmonte, Carmen (2017), Staging Colonialism in the ‘Other’ Italy Art and Ethnography at Palermo’s National Exhibition (1891/92), in «Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz», LIX(1), pp. 87-108

Berger, John (2009), About Looking, London, Bloomsbury

Chamberlain, Muriel Evely (2009), The Scramble of Africa, 2nd ed., London, Longman

Classen, Constance (2012), The Deepest Sense. A Cultural History of Touch, Chicago, IL, University of Illinois Press

Conrad, Sebastian (2008), Deutsche Kolonialgeschichte, Munich, C.H. Beck

Cooper, Frederick (2005), Colonialism in Question. Theory, Knowledge, History, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press

De Napoli, Olindo (2013), The Legitimation of Italian Colonialism in Juridical Thought, in «The Journal of Modern History», 85(4), pp. 801-832

Dekker, Rudolf (2002), Egodocuments and History: Autobiographical Writing in its Social Context since the Middle Ages, Hilversum, Uitgeverij Verloren

Fanon, Frantz (1963), The Wretched of the Earth, London, Penguin Books

Fanon, Frantz (2008), Black Skin, White Masks. London, Pluto Press

Frankenberg, Ruth (1993), White Women, Race Matters. The Social Construction of Whiteness, London, New York, Routledge

Fulbrook, Mary (2011), Dissonant Lives. Generations and Violence through the German Dictatorships, Oxford, New York, Oxford University Press

Hall, Catherine (2002), Civilising Subjects. Metropole and Colony in the English Imagination, 1830-1867, Cambridge, Polity Press

Hall, Catherine (1999), William Knibb and the Constitution of the New Black Subject, in Daunton, Martin, Rick Halpern (eds.), Empire and Others. British Encounters with Indigenous Peoples, 1600-1850, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press

Hill, Patricia, Diane Kirkby, Alex Tyrell (2007), Feasting on National Identity: Whisky, Haggis and the Celebration Scottishness in the Nineteenth Century, in Kirkby, Diane, Tanja Luckins (eds.), Dining on Turtles. Food Feasts and Drinking in History, New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 46-63

Hochschild, Adam (2006), King Leopold’s Ghost. A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, updated ed., London, Pan

Jäger, Jens (2000), Photographie: Bilder der Neuzeit, Tübingen, Edition diskord

Jenssen-Tusch, Harald (1902), Skandinaver I Congo, Gyldendal

Kaplan, Elizabeth Ann (1997), Looking for the Other. Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze, New York & London, Routledge

Kemp, Wolfgang (2011), Geschichte der Fotografie: Von Daguerre bis Gursky, Munich, C.H. Beck

Kiple, Kenneth F. (2007), A Movable Feast. Ten Millenia of Food Globalization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Langbehn, Volker M. (ed.) (2010), German Colonialism, Visual Culture, and Modern Memory, New York, Routledge

Lewerenz, Susann (2007), Völkerschauen und die Konstituierung rassifizierter Körper, in Junge, Torsten, Imke Schmincke (hrsg.), Marginalisierte Körper. Beiträge zur Soziologie und Geschichte des anderen Körpers, Münster, Unrast, pp. 135-153

Luttikhuis, Bart (2013), Beyond Race: Constructions of ‘Europeanness’ in Late-Colonial Legal Practice in the Dutch East Indies, in «European Review of History», 20.4, pp. 539-558

Mangan, James Anthony (2011), Making Imperial Mentalities: Socialisation and British Imperialism, Oxford, Routledge

McCann, James C. (2009), Stirring the Pot: A History of African Cuisine. Athens, Ohio, Ohio University Press

Mecklenburg, Adolf Friedrich Herzog zu (1912), Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil. Bericht der zweiten deutschen Zentralafrika – Expedition des Herzogs Adolf Friedrich zu Mecklenburg, Leipzig

Metcalf, Alida C. (2005), Go-betweens and the Colonization of Brazil, 1500-1600, Austin, University of Texas Press

Mohanram, Radhika (2007), Imperial White. Race, Diaspora, and the British Empire, Minneapolis/London, University of Minnesota Press

Nagl, Dominik (2007), Grenzfälle. Staatsangehörigkeit, Rassismus und nationale Identität unter deutscher Kolonialherrschaft, Frankfurt am Main, Peter Lang

Natermann, Diana M. (2018a), Pursuing Whiteness in the Colonies. Private Memories from the Congo Free State and German East Africa (1884-1914), Munster, Waxmann Verlag

Natermann, Diana M. (2018b), Weißes (Nicht-)Essen im Kongofreistaat und in Deutsch-Ostafrika (1884-1914), in Aselmeyer, Norman, Veronika Settele (hrsg.), Geschichte des Nicht-Essens: Verzicht, Vermeidung und Verweigerung in der Moderne, Berlin, De Gruyter, pp. 237-264

Natermann, Diana M. (2022), Colonial Masculinity: Monarchy, Military, Colonialism, Fascism and Decolonization, in Almagor, Laura, Haakon Ikonomou, Gunvor Simonsen (eds.), Global Biographies: Lived History as Method, Manchester, Manchester University Press, pp. 62-81

Pakenham, Thomas (1992), The Scramble for Africa. White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1878 to 1912, New York, Harper Collins

Palmstierna, Nils (1967), Swedish Army Officers as Instructors in African and Asian Countries, in «Revue Internationale d’Histoire Militaire», 26, pp. 45-73

Panofsky, Erwin (1980), Aufsätze zu Grundfragen der Kunstwissenschaft, edited by Oberer, Hariolf, Egon Verheyen, Berlin, Volker Spieß

Panofsky, Erwin (1997), Studien zur Ikonologie der Renaissance, 2nd edition, Cologne, DuMont

Paul, Gerhard (2006), Von der historischen Bildkunde zur Visual History. Eine Einführung, Flensburg

Pilcher, Jeffrey M. (2006), Food in World History, in Stearns, Peter N. (ed.), Themes in World History, New York, NY, Routledge

Presser, Jacques (1968), Ashes in the Wind. The Destruction of Dutch Jewry, London, Souvenir Press

Prince, Magdalene von (1908), Eine Deutsche Frau Im Innern Deutsch-Ostafrikas, 3rd ed., Berlin, Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn

Quattrocchi, Umberto (1999), CRC World Dictionary of Plant Names. Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology, Boca Raton, CRC Press

Rizzo, Lorena (2013), Shades of Empire: Police Photography in German South-West Africa, in «Visual Anthropology», 26.4, pp. 328-354

Roberts, Andrew Michael (2001), Conrad and Masculinity, New York, Palgrave

Said, Edward W. (1978), Orientalism, London, Penguin

Sandler, Willeke (2013), Deutsche Heimat in Afrika: Colonial Revisionism and the Construction of Germanness through Photography, in «Journal of Women’s History, 25.1, pp. 37-61

Schulze, Winfried (ed.) (1996), Ego-Dokumente: Annäherung an Den Menschen in Der Geschichte, Berlin, Akademie Verlag

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty (1988), Can the Subaltern Speak?, Basingstoke, Macmillan

Sontag, Susan (2008), On Photography, London, Penguin Classics

Steinbach, Daniel Rouven (2011), Carved out of Nature. Identity and Environment in German Colonial Africa, in Brimnes, Niels, Christina Folke Ax, Niklas Thode Jensen, Karen Oslund (eds.), Cultivating the Colonies. Colonial States and Their Environmental Legacies, Athens, OH, Ohio University Press

Tosh, John (2005), Manliness and Masculinities in Nineteenth Century Britain. Essays on Gender, Family and Empire, Harlow, Pearson Longman

Wylie, Diana (2001), Starving on a Full Stomach: Hunger and the Triumph of Cultural Racism in Modern South Africa, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press

Zocchi, Benedetta (2019), Italian Colonialism in the Making of National Consciousness: Representations of African Natives, in «Storicamente», 15, pp. 1-27

[1] For more on Othering and colonial subalterns, see Said (1978); Spivak (1988).

[2] For more on the use of written and visual colonial ego-documents in a Belgian and German colonialism context: Natermann (2018a).

[3] On the issue of socialisation as of birth and generational memory construction, see the works by Émile Durkheim and Maurice Halbwachs. From a more contemporary perspective within the field of memory studies, I here recommend the scholarly output by Aleida Assmann.

[4] See Hill/Kirkby/Tyrell (2007); Pilcher (2006); Wylie (2001). For more on imperial whiteness see Mohanram (2007).

[5] Eight of the nine team members took photographs in Africa with the artist E. Heims being the exception.

[6] The term ‘ego-document’ was coined by Jacques Presser who proposed to use the neologism ‘ego-document’ for private forms of the autobiographical. His approach focused on the more literary aspect of ego-documents and was contrary to the usual analysis style applied with the more official sources in the hierarchy of historical documentation. Ego-documents can be diaries, travelogues, correspondence, photographs, and memoirs. Dekker (2002); Presser (1968); Schulze (1996).

[7] Also referred to as imperial gaze. Kaplan (1997).

[8] See Berger (2009); Sontag (2008); Panofsky (1997), pp. 207-225.

[9] Mecklenburg (1912), pp. 1-3. A year later the two tomes were also published in English: From the Congo to the Niger and the Nile; an account of the German Central African expedition of 1910-1911, London, Duckworth & Co., 1913, 2 vols.

[10] Walter von Wiese und Kaiserswaldau (1879-1945) was a German military man who, at the time of his two Africa expeditions with the Duke of Mecklenburg, held the rank of captain in the German colonial troops in German East Africa. He was known for his topographic pictures of the Massaiplanes. In 1907/08 he was the leader of the Deutschen Wissenschaftlichen Zentralafrika-Expedition. During the 1910/11 expedition he worked as an ethnographer along the Ubangi and Nile rivers and was the co-writer of the Duke of Mecklenburg’s book Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil, 1912.

[11] Hermann Schubotz (1881-1955) was a zoologist. From 1905/07 he worked as an assistant at the Zoological Institute of Berlin University. Like von Wiese zu Kaiserswaldau, Schubotz too accompanied the Duke of Mecklenburg on both Africa expeditions in 1907/08 and 1910/11. Schubotz was the editor of Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der deutschen Zentralafrika – Expedition 1907/08, unter Führung Adolf Friedrichs Herzogs zu Mecklenburg, Bd. III u. IV Zoologie, Leipzig, 1911, and assisted in writing the book Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil by the Duke of Mecklenburg.

[12] Apart from the occasional mentioning of Otto Röder in the two-tome publication Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil by the Duke, nothing much is known about this person.

[13] Apart from the occasional mentioning of the butler Mr Schmidt in the Duke’s book Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil, nothing much is known about this individual. Unfortunately, not even his first name.

[14] Apart from the occasional mentioning of the Ernst M. Heims in the the Duke’s Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil publication, nothing much is known about this person.

[15] Karl Albert Haberer (1861-1941) was a medical doctor and specialised in tropical diseases.

[16] Arnold Schultze, Oberleutnant a.D., Dr. phil., (1875-1948). Initially an Officer in the Prussian Army, he was later a member of the British-German 1903/04 Jola-Chadlake-Expedition. In 1905/06 he was an Officer in the German Imperial Troops in Cameroon after which he studied geography and did his PhD in Bonn in 1910. As a member of the Duke’s 1910/11 Africa expedition he travelled to southern Cameroon, Fernando Póo, and Annobon. His writings include Das Sultanat Bornu mit besonderer Berücksichtigung von Deutsch-Bornu, Essen 1910, and he assisted with the Duke’s book Vom Kongo zum Niger und Nil.

[17] Gottfried Wilhelm Johannes Mildbraed (1879-1954) is known for authoring a monograph and taxonomic treatment of the family Stylidiaceae in 1908 as part of the unfinished Das Pflanzenreich series. The genus Mildbraediodendron was named in his honour (Quattrocchi, 1999, p. 1691).

[18] The photos for this project were taken during an expedition led by Duke Adolf Friedrich Mecklenburg and seven of his eight team members. The research center “Hamburg’s (post-)colonial Legacy” at Hamburg University and the MARKK – Museum am Rothenbaum. Kunst und Kulturen der Welt – joined forces to be the first to study the expedition’s photographs. Long-term goals were to outline the collection’s social, cultural, and public importance to Germany’s colonial history and their digitalisation to create a public online database.

[19] See Mecklenburg (1912), tome 1. The above numbers exclude the profile photographs of the expedition members and the books’ cover pages.

[20] See Mecklenburg (1912), tome 2.

[21] See Natermann (2018b).

[22] Wylie (2001), Pilcher (2006), Hill/Kirkby/Tyrell (2007), Kiple (2007), McCann (2009), Steinbach (2011).

[23] Whilst Mr Schmidt is not named as a photographer in the MARKK’s inventory list, according to the Duke’s diary, Mr Schmidt did take at least a couple of photos. It seems that these photos were not listed under his name but as ‘Innerafrika’. For photograph in question see Innerafrika_3224, Innerafika_3225, Innerafrika_3226. For diary entry see MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, p. 111.

[24] Whilst the glass plate negatives were addressed to the MARKK, other artefacts like hunting items or Central-African clothes and jewelry were sent to the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt a.M.

[25] German: «Spiegel-Reflex-Kamera», See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, p. 38.

[26] German: «[…] um einige Photos vom Ubangi und meinem Hause zu machen […] Die Entwicklung zeigte, dass sie gut geworden sind». See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, p. 54.

[27] Hochschild (2006).

[28] For a variety of studies concerning the (re-)creation of socio-cultural values throughout the nineteenth century, please see following selection of readings Frankenberg (1993), Langbehn (2010), Mangan (2011), Tosh (2005).

[29] See chapters 1 and 2 of Mohanram (2007).

[30] Fulbrook (2011), p. 10.

[31] This is also seen in the above mentioned collective memory theory à la Maurice Halbwachs.

[32] For more on the specific case of German diary writing and colonialism see Reimann-Dawe (2011).

[33] Fulbrook (2011), p. 10.

[34] Fulbrook (2011), p. 11.

[35] Hall (1999), p. 303. For more on elaborate use of identity creation: Hall (2002); Cooper (2005).

[36] See Said (2003); Fanon (2008) and (1963).

[37] Natermann (2018a).

[38] For more on theory behind colonial go-betweens in early-modern overseas European colonialism see Metcalf (2005).

[39] The visual source analysis is done in accordance with Erwin Panofsky’s method and works by Jens Jäger. See Jäger (2000), pp. 65-85; Panofsky (1980) and (1997), pp. 207-225.

[40] Engl.: Heims-Röder and Sultan Sanda. Photographer: Röder. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg.

[41] Mecklenburg (1912), Chapter 8.

[42] German: «Am Nachmittage kam Chefu Sanda von Dikoa, um uns zu begrüßen, und seine Geschenke zu überreichen, bestehend aus drei Schafen, zwanzig Hühnern, Eiern, Brot und Honig. Da gerade mein Geburtstag war, musste ich über diese echt afrikanischen Geschenke herzlichst lachen. Ich ließ meine Koffer mit Seidenstoffen auspacken, und befriedigt zog der Gewaltige von dannen». Mecklenburg (1912), p. 196.

[43] German: «Ist auch Chefu Sanda heute noch Sultan von Dikoa, so ist er, wie die anderen Sultane von Karnak-Logone, Kusseri, Gulfei und Manadara, für uns [Deutsche] nur eine Art Puppe». Mecklenburg (1912), pp. 197-198.

[44] Classen (2012), p. 73.

[45] The theory of the sensory scale of senses was founded by natural historian Lorenz Oken. Cited from Classen (2012), p. xii.

[46] Kiple (2007), p. 225.

[47] Engl.: Camp scene. Photographer: von Wiese zu Kaiserswaldau. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg.

[48] Another then often applied scientific tool were the so-called human zoos/exhibitions in Germany, Italy, and other parts of Europe. See Belmonte (2017); Lewerenz (2007).

[49] The MARKK owns a copy of the expedition’s photographic inventory list. The list indicated in about 90% of the cases who the photographer was, when and where the photograph was taken as well as the negative’s size.

[50] German: «kinematographiert». See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, pp. 68, 83, 132.

[51] Kusseri is a town situated in Northern Cameroon close to the Cameroonian-Chad border. At the time of the Mecklenburg-Expedition, it was better known as Fort Kousséri and run by French colonisers. Sultan Kusseri was the local indigenous leader.

[52] German: «alle großen Sultane mit einer Gefolgschaft von etwa 20.000 Mann». See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, p. 132.

[53] Photographer: Haberer. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg.

[54] Photographer: Haberer. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg.

[55] German: «Das mit luftiger Veranda versehene Haus des Residenten, sowie die Häuser der Unteroffiziere, [sind] sämtlich aus Stein gebaucht uns sauber weiß getüncht». Mecklenburg (1912), p. 68.

[56] See Kaplan (1997).

[57] The Duke was in this sense a remarkable individual that managed to always stay afloat despite changing political and social systems. See Natermann (2022).

[58] See Sontag (2008).

[59] In her work, Zocchi takes the Italian route by focusing on written sources yet also placing the Italian racially discriminatory path of othering the African subject and an Italian colonial identity. Zocchi (2019).

[60] See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1, pp. 30, 71, 91, 122, 128, 130, 132, 134, 155, 158, 184, 189, 192, 193, 198, 208, 210, 211, 214, 223, 224, 228.

[61] Engl.: His Highness, Prof Haberer and Heims having breakfast. Photographer: Mecklenburg. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg.

[62] Engl.: At the breakfast table in Molundu. Photographer: Mildbraed. © Museum am Rothenbaum (MARKK), Hamburg. Molundu is a town in Cameroon at the Cameroonian-Congolese border.

[63] The here mentioned diaries are archived at the MARKK in Hamburg. See Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.1; and Tagebuch MARKK – Herzog A. Friedrich zu Mecklenburg-Expedition – HER 2.2.1.

[64] The other topics were the aforementioned big game hunting and burdens of traveling as well as comparing different European nation’s colonising techniques.

[65] More on colonial rulemaking and legal orders being inherently racist, see De Napoli (2013).

[66] Nagl (2007).

[67] Luttikhuis (2013), p. 542.