The paper offers some reflections on the productivity of complicated entanglements of art and law for those engaged with contemporary challenges of legal pluralism. The context for these reflections is Canada, with its fraught colonial history, and the legacy of its (non)engagement with Indigenous peoples and their legal orders. Here, situated in ongoing conversations about ‘truth’ and ‘reconciliation’, the example of The Witness Blanket, a work of art responding to a deep failure of law, is first taken up. Then, The Witness Blanket Stewardship Agreement is explored, as a piece of law, responding to the needs of a piece of art. In each case, the focus is on the ways both art and law, as deeply collaborative practices, can open up pathways for more productive intersocietal forms of agreement to guide people in working and living with each other in worlds marked by legal pluralism.

L’articolo offre alcune riflessioni sulla produttività degli intrecci tra arte e diritto per coloro che sono impegnati nelle sfide contemporanee del pluralismo giuridico. Il contesto di queste riflessioni è il Canada, con la sua storia coloniale travagliata e l’eredità del suo (non) impegno con i popoli indigeni e i loro ordinamenti giuridici. Qui, nell’ambito delle conversazioni in corso sulla “verità” e sulla “riconciliazione”, viene dapprima preso in considerazione l’esempio di The Witness Blanket, un’opera d’arte che risponde a un profondo fallimento del diritto. In seguito, viene esaminato il The Witness Blanket Stewardship Agreement, un testo di legge che risponde alle esigenze di un’opera d’arte. In ogni caso, l’attenzione si concentra sui modi in cui sia l’arte sia il diritto, in quanto pratiche profondamente collaborative, possono aprire percorsi per forme di accordo intersociale più produttive, per guidare le persone a lavorare e vivere insieme in mondi segnati dal pluralismo giuridico.

CONTENUTI CORRELATI: Art - Indigenous Law - Stewardship - Residential School - Ceremony - arte - diritto indigeno - gestione - scuola residenziale - cerimonia

- 1. Introduction - 2. Art as a Response to the Failure of Law - 2.1. «Getting rid of the Indian Problem»: The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement - 2.2. Art and Commemoration: On the Making of The Witness Blanket - 2.3. Art and the Generating of New Legal Challenges: On Finding a Home - 3. Law as a Response to the Needs of Art (a Gallery Walk Through the WBSA) - 3.1. The Written Commitments - 3.1.1. Refocusing the Legal Subject - 3.1.2. Money Matters - 3.1.3. Responsibilities and Commitments - 3.1.4. Duration, Temporality, and Endings - 3.2. Oral Culture, Art, and the Role of Ceremony - 4. Conclusion: Observations on Attending a Feast - Bibliography - Appendix: An Agreement Concerning the Stewardship of the Witness Blanket – A National Monument to Recognize the Atrocities of Indian Residential Schools - Appendix A: Kwakwaka’wakw Ceremony - Appendix B: Definitions - Appendix C: Past, Present, Future - Appendix D: Financial Agreement - FOOTNOTES

Prelude: A moment in time. After a three hour road trip full of laughter, stories, and stopping for snacks, our group of travellers arrive at Kumugwe, the Bighouse on the traditional territory of the K’omoks First Nation[1]. This is my first visit to this space. We follow others from the parking lot, and enter through the wooden door. The pale light of the crisp overcast October morning dims as we move into the ceremonial hall, the fire crackling in the centre of the room, filling the space with a much warmer flickering light. Across the room, massive Thunderbirds with their wings unfurled rise from the top of the carved house poles which hold up the beams of the roof, drawing the eye up to the opening at the centre where smoke rises to the sky and light filters back in. We have entered into a different space, one holding us in an embrace of bare earth and wood. The sounds of the world outside fade away, to be replaced by the sound and scent of fire, and the murmur of voices as we find a seat on the wooden benches lining the wall, and wait for the ceremony to begin.

In contemporary Canada, some of the most pressing legal problems centre on the legal status of Canada itself, as a colonial settler state. As articulated in the five-volume Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, at issue are questions about the fragility of legal foundations in Canada’s assertion of jurisdiction over Indigenous lands and peoples, particularly in the face of the reality of the many pre-existing Indigenous legal orders and traditions[2]. Questions about ‘the honour of the crown’, the ‘duty to consult’, and ‘land back’ are part of the language of our times. With the acknowledgement by the Canadian courts of the pre-existing and continuing reality of Indigenous legal orders, legal pluralism is an unavoidable fact. The questions before the courts and the legislatures are no longer ‘if’ Indigenous legal orders exist but are rather about ‘how’ settler and Indigenous legal orders will negotiate productive and lawful ways of living in a shared world.

This new legal landscape, with its challenges to Canada’s assertion of jurisdiction over Indigenous peoples, finds articulation in the courts, in Parliament, in classrooms, in the media, and in the arts. An important part of this conversation involves the question of ‘national memory’; how do Canadians (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) begin to tell a more accurate story of our own history, a history of the land, its peoples, the Canadian state, and the ways law has been used as a tool in support of dispossession and (cultural) genocide[3]?

In this paper, I take up these conversations at the intersection of law and art. In section 2, I situate the discussion in the Canadian context with its history of Indigenous children being taken from their families to be placed in residential schools. This will include a discussion of the largest class action in Canadian history, one that resulted in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. This agreement produced a call for art in the form of projects of commemoration and national memory. One of these is The Witness Blanket.

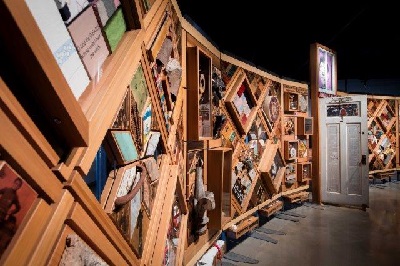

Fig. 1 – The Witness Blanket; photo credit: Aaron Cohen

In this conversation about The Witness Blanket, I raise questions about the ways that, within many Indigenous legal orders, art should be understood as not simply artistic object but as an act of governance, or as part of the fabric of law. The Witness Blanket, in this account, is an important piece of legal art: a work of commemoration, responding to a problem of a failure of law (that is, the legal structures supporting and enabling a cultural genocide, and resulting in the largest class action in Canadian history).

In Section 3, I shift the direction of focus, and explore how this particular piece of art has participated in the development of a new and decolonial approach to legal relationships, in the form of the Witness Blanket Stewardship Agreement. This agreement draws both settler and Indigenous legal orders into relationship through the art itself. In this section, we will take a form of ‘gallery walk’ through this Agreement, exploring how it invites us into a differently structured relationship of art and law.

Let us begin with the problem of Canada’s colonial history, focusing on the legal framework through which Indigenous children were removed from their families and communities, and were placed in residential schools[4]. These schools were one piece of a larger colonial project through which Indigenous societies were dispossessed of their lands, economies were disrupted, practices of law and culture were rendered criminal, and people (and particularly women) were stripped of their citizenship[5].

An entry point might be 1876, with the first Indian Act, with its assertion of federal government authority over “Indians” in Canada. Those early years saw the beginnings of government cooperation with Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches to establish a system of residential schools. By the turn of the century, amendments to the Indian Act made attendance at residential schools mandatory. Duncan Campbell Scott, one of the proponents of the system, saw the schools as a way to «get rid of the Indian problem»[6]. These schools, which were co-managed by the Canadian Government and four different Church organizations, were widely understood as having a mandate to «kill the Indian in the child»[7]. This was not mere metaphor. As early as the 1920s, it was known that a larger than average number of deaths happened at these schools[8]. For many children, the killer was often preventable diseases, malnourishment, unsafe conditions, and crowded conditions in the schools. And yet, Duncan Campbell Scott wrote,

Well before the last school closed in 1996, student survivors of the schools had begun to initiate legal actions against governments and churches to push for recognition of the harms inflicted and experienced through the schools. As the number of claims mounted, it became clear that the volume of cases would result in the clogging of the courts for years to come. The cases were finally joined into what was the largest class action in Canadian history, brought on behalf some 150,000 still living adult survivors of Indian Residential Schools against the Canadian Government and four church organizations[10].

Pressure mounted for the government to seek a forum for alternative dispute resolution, which finally resulted in the 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA). The IRSSA recognized the damage inflicted by residential schools and established a multi-billion-dollar compensation fund made up of five components. The first three of these were only available to former residential school students covered by the IRSSA[11]. Two of the components, however, were directed to the larger questions of Canadian national memory. The first of these was the constituting of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was allocated $60 million to provide opportunities for accounts of the schools to be publicly shared; to raise public awareness; to create a comprehensive historical record; to create a research centre. There was also $20 million set aside for projects of Commemoration, to honour and publicly acknowledge the experiences of former students, families, communities.

The point is that the Survivors of the schools re-allocated a total of $80 million that would have otherwise been available to them as compensation, to the larger project of Canadian national memory. In thinking about how to respond to the harms of what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission would document as a cultural genocide[12], the survivors asked for not only words, but also for art. This was significant given a colonial history in which, through what is known as the Potlach Ban, Indigenous public ceremonial practices of feasting, dancing, and gift exchange were criminalized[13]. People participating in these practices were jailed; ceremonial regalia, masks, other treasured objects that were part of the practices of feasting were confiscated and often sold to museums or other collectors[14].

The Potlach Ban aimed to disrupt central indigenous cultural/legal institutions. Amongst the Gitksan, for example, legal jurisdiction is exercised through the feast. The feast (what others may refer to as the potlach), «is a complex political, legal, economic, and social institution in which the main business of the hosting House is transacted and formally witnessed by the guest Houses»[15]. In former times, feasts were held for all major legal, social, and political transactions, including the raising of (totem poles).

Even following the lifting of the Potlach Ban in the 1950s, there has been a persisting failure within the Canadian legal system to acknowledge the significance of artistic production in the ways which Indigenous legal knowledges have been carried and enacted[16]. An infamous contemporary example of this failure occurred at the trial level during the ground-breaking Delagamuukw trial, where Gitxsan elders, asked to provide evidence of their law, asserted that the law (adaawk) was carried in song, and had to be sung[17]. Justice McEachern, in response to the assertion that this law be sung for the Court, argued that he could not hear the songs as evidence, asserting that he had a ‘tin ear’[18]. In this context, what was at issue was the judge’s incapacity to see songs, crests, stories, masks, or dances as not simply ‘representations’ of law, but as elements of law.

In many North American Indigenous legal orders, there are important and powerful relationships between what some describe as ‘art’ and some describe as ‘law’. At the opening of the exhibit Testify! Indigenous Laws + the Arts, Nlaka’pamux lawyer (and now judge) Ardith Wal’petko We’dalx Walkem talked about the close relationship between law and art for many Indigenous peoples[19]. In her nation, she said, when a complex problem engages the people, the artists are brought in. Artists are, in a sense, also lawyers. In engaging with Indigenous legal orders, then, it is crucial to understand the different ways that law is recorded, generated, validated, enacted and transformed in art. Art is not simply object, but also a process of engagement, a carrier of history, a teacher of law[20]. In working across legal orders, we are invited to productively disrupt fixed assumptions about what constitutes ‘art’, what constitutes ‘law’, and about the relationships between them. This, then, is the context for understanding how and why the survivors of the Residential Schools, in the IRSSA, focused on the importance of art in responding to the Canadian state’s failure of law.

Artist Carey Newman responded to the IRSSA’s call for projects of commemoration. Newman (whose traditional name is Hayalthkin’geme) is Kwagiulth of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation on his father’s side, and descended from English, Irish and Scottish settlers on his mother’s side. Newman, whose own father had attended residential school from the time he was 7 years old until 19, was firmly situated in the complicated and entangled spaces generative for non-linear and embodied thinking. What kind of ‘art’ or project of memory, Newman asked, could adequately respond to the systemic violence and the human rights violations involved in the histories and aftermath of the Indian residential schools regime[21]? How might art speak to a colonial project that involved a denial of Indigenous legal orders across the nation, and across generations? How might one respond to the failure of law at the heart of the colonial project, a failure which generated such profound injuries and ongoing intergenerational trauma? How might one produce a work of commemoration able to carry the weight and variety of stories to be told, and to do so in a way that accorded with the structures of Indigenous legalities?

Fig. 2 – The Witness Blanket; photo credit: Aaron Cohen

What Carey Newman produced was The Witness Blanket[22]. The Blanket is made up of carved cedar panels, which incorporate 880 objects gathered from residential schools, churches, government offices, and individuals (survivors, their families and loved ones, teachers, officials and more). It stands 3.2 meters at its highest point, and stretches 12 meters wide. The process of its construction stretched over a period of 2 years, as a team of people travelled across the country, to both gather the objects, and also to hear and record the stories that came with those objects[23]. The goal was to find at least one thing from each of the 139 schools spread across the country, which also meant being creative (given that some of the buildings that housed the schools no longer existed).

The Blanket was woven to include objects from traditional structures (like big houses, sweat lodges and tipis) as well as from urban and contemporary Indigenous places. It includes bricks, brass doorknobs, plates and cutlery, a school uniform, a child’s shoe collected from the forest floor. It includes school records, yearbooks, graduation certificates, building inspection reports, pamphlets outlining school rules, invoices for coal to heat the school in winter. At its centre is a door taken from one of the schools on the cusp of its demolition. It includes an old wooden desk onto whose surface a slideshow of images and documents is projected. It also incorporates items that link Newman and his family directly to the Blanket: the handprint of his daughter on the back of a door, a piece of tree from the school his father had attended, a braid of his sisters’ hair[24].

Fig. 3 – Braids on the Blanket; photo credit: Jessica Sigurdson

This work of art – this work of memory – draws deeply on aspects of law that have deep connections in the Salish legal traditions of Newman’s family: cedar, blankets, and witnessing. Cedar, often referred to as the ‘tree of life’ is deeply integrated into Coast Salish society, with all parts of the tree finding use[25]. Blankets have broad resonance in most cultures around the world (and are wrapped both around the newly born, and the dead), but they also have specific cultural and legal significance in many West Coast legal traditions, linked to practices of identifying lineages, and formalizing and publicly validating people and events[26]. And the objects in the Blanket themselves stand as witnesses, drawn together in ways that could capture the magnitude of events and stories to be remembered. The idea of witnesses, again, resonates in all legal traditions, and in particular ways in West Coast legal orders[27].

The Witness Blanket, drawing these elements together, invites its audience into engagement. It is something that requires one to walk around, along, through, and behind. There is a door to pass through, there are books whose covers one must bend down to read, there is a table with papers, a piece of a tree, a child’s shoe. Each object invites the viewer ask questions, or to consider what the image captures, and why it is there. It invites the viewer into relationship.

The Witness Blanket was first exhibited in Victoria, BC in 2016. It then began to travel across the country, spending time in different cities. As Newman pointed out in an interview, such travels do require attention to maintenance, and repairs were necessitated each time the Blanket was set up or taken down. At some point, he began turning his attention to the question of where the Blanket could spend a longer sojourn. But in thinking about this question, he found himself struggling with the available western legal languages in which to address some deep challenges. If the Blanket was to find a home at a museum, what would be the terms of the legal agreement governing both that move, and the kind of care that the Blanket would require?

His experience of assembling the Blanket had made visible that the language of ownership was profoundly inadequate to describe his relationship to it. The objects in the Blanket were put into Newman’s care by Indigenous peoples from many different Indigenous legal orders across Canada. What would it mean to then transfer “ownership” of the Blanket (and all those objects) through an agreement for sale? And what sum could possibly capture the value in the Blanket? Another puzzle, he had noted, was that the construction of the Blanket was paid for by the Survivors (who allocated $20 million of their own settlement to make such projects possible). Newman had already been paid by the survivors to produce the Blanket. Was he now in a position to profit from the gift that had been given by the Survivors? In this context, how might he approach the question of financial agreements involved in a possible transfer[28]?

Another problem was how to think about the maintenance and care of the Blanket. Museums of course have extensive protocols for objects in their care. However, those protocols generally focus on the art as ‘object’. But within many Indigenous legal traditions, the dividing lines of animacy differ from those of western law. Trees, in particular, have animacy[29], and so there are often very specific cultural protocols of care for works like masks which are carved from wood[30].

The Blanket, in this sense, was less ‘object’ than ‘subject’. And it was a subject composed of materials from the physical world, the world of fabricated objects, and the world of stories. Both stories and songs, within most Indigenous legal orders, operate in ways that presume specific practices and protocols for both telling and listening[31]. So how, then might Newman be able to find a museum partner able to enter into an agreement that would ensure that the Blanket received not only care as understood within conventional museum practice, but also within a Kwakwaka’wakw world view?

Fig. 4 – A lost child’s shoe finds a home in the Blanket; photo credit: Jessica Sigurdson

In its travels, the Blanket had already spent time in the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (CMHR) in Winnipeg, Manitoba. And so, Newman opened a conversation with archivist Heather Bidzinski, Anishinabek lawyer Jennifer Nepinak, and Museum CEO John Young. This group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous lawyers, artists, archivists, and administrators understood that The Witness Blanket was a response to a prolonged period of juridicide – an attempt by Canada and Canadians to erase Indigenous legal orders. Thus, a contemporary legal response to the care of the Blanket could not come from within Canadian common law alone. Over a period of years, they went back and forth, staying in conversation, capturing ideas, learning about and with each other, and finally arriving at a form of legal agreement that might do this important work, responding to the needs of the Blanket itself.

The resulting Witness Blanket Stewardship Agreement (WBSA) aimed create a space for lawful action from within both common law and an Indigenous legal order. This is made explicit in the written text: «This agreement will be guided by both Kwakwaka’wakw traditional legal orders and Canadian Common Law». But what might this mean? The WBSA affirms the parties’ understanding of the complexity of this decision:

The written portion of the WBSA (which is reproduced in full as an Appendix to this Article) was first signed at a ceremony at the Canadian Museum of Human Rights. And then, on October 16, 2019, the WBSA was finalized through a traditional ceremony at Kumugwe, the K’omoks First Nation Bighouse on Vancouver Island. As news releases pointed out, this was a historic moment – the first time in Canadian history that a federal Crown corporation had ratified a legally binding contract through Indigenous legal traditions[32].

The WBSA, situated at the intersection of art and law, echoes the legal creativity and collaborative spirit present in the Witness Blanket itself. The WBSA, in my view, holds great promise as a pedagogical model of what is possible where people from different legal orders sit longer in the presence of art to help re-orient our understandings of lawfulness and our place within it[33]. In this section we will engage in something of a ‘gallery walk’ through the WBSA. In section 3.1, we will focus on the written commitments, exploring 4 elements of interest: first, subjects and objects; second, money matters; third, the relationship of rights and responsibilities; and fourth, duration and endings. In section 3.2, the focus will shift to the oral commitments in the WBSA, rooted in ceremony with its embodied experiences of sight, sound, movement and feasting. This will allow us to pose questions about art and ceremony as ways of learning and practicing law, and about what it means to have ongoing obligations to return to the spaces of ceremony. The goal is to open space for examining a creative form of law-making that responds to a work of art/commemoration that is itself a complicated and creative response to a failure of law.

Because names are important, let us begin there. The full title of the WBSA is, An Agreement Concerning the Stewardship of the Witness Blanket – A National Monument to Recognize the Atrocities of Indian Residential Schools. The title first names the context by acknowledging an atrocity. It then structures the relationship between Carey Newman, the Museum, and the Blanket in a very specific way. The common law convention would be to view the blanket as object, and the Museum and Newman as subjects of a particular kind: a ‘buyer’ and a ‘seller’. This convention is one that constructs the relationship through a specific kind of market lens, where each of the two primary parties is bargaining around how much (or how little) they can pay for an object, and what rights or entitlements they have with respect to how the object is to be transferred and/or treated by the parties. One might imagine, for example, clauses regarding exhibition, or maintenance, insurance, or copyright.

Fig. 5 – John Young and Carey Newman signing the written portion of the WBSA

Fig. 5 – John Young and Carey Newman signing the written portion of the WBSA

at the CMHR; photo credit: Keith Fraser

Here, the title points us to a different subject/object orientation. It moves us from the language of markets to the language of relationship: providing stewardship to the Witness Blanket. The language of stewardship, not unknown in the common law world, would conventionally point in the direction of children, or the infirm, or lands and resources in need of care. The WBSA-Appendix B: Definitions gives shape to what the parties mean in using the language of Stewardship and Stewarding:

The Blanket is described animate – as having agency. This is also made explicit in the definition given for the word “Lodging”:

These two definitions signal a non-conventional approach to the Witness Blanket. It is not simply that the Blanket is described as in need of care, but also that it is described as a rights holder. The Witness Blanket, defined thus, includes elements that, whatever one’s philosophical beliefs, are to be treated as living beings. While not completely disavowing the concept of ownership as it is conventionally understood (in either legal order), there is a diffusing of its pull both through the definitions above, and through an explicit statement that any ownership claims (as they might be understood with Canadian common law) are distributed («no one person owns The Witness Blanket»). This orientation is reinforced in one of the 5 principles agreed to by both parties on the first page of the WBSA:

Several things stand out to one trained in a Western legal tradition, and primary here is a way of thinking about what rights are, and who possesses them. In the WBSA, the only person with ‘rights’ is the Witness Blanket itself, which is identified as a subject, and not an object. While this is unusual in the context of the art world, the notion that other more than human entities can be spoken of as agents is not without precedent. Consider the Whanganui River in Aotearoa (New Zealand), now identified as a legal person. Or indeed, the identification of corporate entities as legal persons. In this context, the Witness Blanket is a rights holder, and the Museum and the Artist are positioned in terms of their shared responsibilities towards the Blanket. Note also here the use of the phrase ‘in the best interests,’ which in North America is used primarily in the context of those who hold fiduciary obligations with respect to others (whether children, the infirm, or the corporate person).

Though there is a decentring or re-orienting of the Blanket as an agent rather than only an object, the WBSA does engage with questions about money. In the conventional form, a Museum would be making a payment to the Artist for the art that was acquired. The parties here did agree that money would change hands. But recall the earlier conversation about the ways in which the Witness Blanket was already funded/financed by the Survivors of the Residential Schools. The WBSA-Appendix D: Financial Agreement addresses the question of money. It opens with a mutual acknowledgment that there is no way to accurately reflect ‘the value’ of the Witness Blanket: «its value is both immeasurable and cannot be monetized». And thus, the Museum pays a fee to the Artist not for the Witness Blanket itself, but rather «in consideration of the opportunities which this collaborative stewardship represent for the Museum». It is worth pausing here: there is no transfer of ownership, no purchase of an object. The Museum transfers money to the Artist to acknowledge the value of being in a relationship of collaborative stewardship. These monies do not represent the ongoing costs of this stewardship (i.e. curating, location, upkeep, signage, lighting, floor space, staff, etc.), but are in addition to those. Further, the Museum commits itself to not only an initial payment of $250,000 but also to making its best efforts at raising an additional $500,000. The Artist, for his part, commits to putting the entirety of this amount (somewhere between one-quarter and three-quarters of a million dollars) towards a legacy project to take the gift given by the survivors and pass it forward into the future. In short, both the Museum and the Artist commitment themselves to generating funds for this purpose.

With the Witness Blanket as the ‘subject’ of attention, one thinks differently about the ‘object/objective’ of the WBSA. The Artist and the Museum are not so much negotiating terms as they are setting out an approach to the shared care of the Witness Blanket. Much of the WBSA focuses attention on questions that are pressing in the context of Art/Law (how to care for art, who gets to see it, how it travels?). Page 2 of the WBSA sets out a list of responsibilities. What we see is a list of shared problems articulated as commitments: how to provide lodging and care; how to work towards common understandings of shared responsibilities; how to approach conservation and preservation; how to curate stories to travel with the Blanket; how to address reproductions and traveling exhibitions; how to respect cultural protocols around care; decisions about the Artist’s appearances; how to plan for changes in specific decision-makers (from the Museum and the Artist’s family) over time.

Notable in this list of commitments is the use of verbs that direct attention to mutual understanding, collaboration and ongoing work between the parties in the process of implementing those commitments. In the list of commitments on p. 2 of the WBSA, note the recurrence of phrases like: ‘will work with’, ‘commits to caring for the Witness Blanket’, ‘understands and honours the responsibilities’, ‘will provide recommendations’, ‘will work in collaboration with’, ‘in discussion with’, ‘will collaborate in the development of’, will provide guidance, will support, will work together.’ The response to the challenges posed by a work of art such as the Witness Blanket is an orientation towards a collaborative practice from the outset. One might note here a certain looseness with respect to specifics: the focus is less on the specific decisions that either party might make, than on articulating assumptions about the processes that will structure their shared decision-making process.

In most contracts of the sort emerging in the common law world, there are provisions to deal with conflicts, or disagreements about decisions. One might thus expect to see some sort of arbitration clause (to refer some kinds of conflicts to a neutral arbiter), or a choice of law clause (to prioritize one or the other of the legal orders in the context of certain kinds conflicts). Conventional clauses of this sort do not appear in the WBSA. The closest thing is a clause which sets out the processes by which the parties will continue to strengthen their relationship, in ways that will enable them to do the hard work of sorting out most differences themselves. On page 3 of the WBSA, one sees this:

Note here that the primary focus is on the commitment to their relationship (which is focused on collaborative stewardship). This is sustained through two practices of review: an annual review of the document (an expected practice of ongoing governance in many incorporated societies), and a practice of renewal feasts (an expected practice for maintaining partnership and treaty relationships in many Indigenous legal orders). In both cases, these are practices aimed at maintaining common understandings so as to avoid the emergence of conflict. Further, such practices of renewal and review are articulated as the foundations for the parties to mutually agree to changes in how they wish to approach their shared stewardship.

Let us finally turn to the question of time. How long is this shared stewardship expected to continue? On p. 3 of the WBSA we see this:

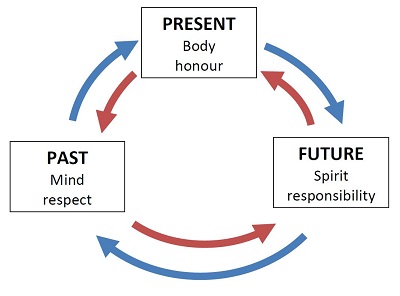

A first point here is to note the language of seven generations in describing the intended duration for the Agreement. The phrase ‘seven generations’, to modern ears, might resonate with the familiar principle of Haudenosaunee law, that embeds decision-making in a context that draws in the needs of community seven generations forward. Such a period of time might be expected to run forward for something like 150 years. This approach to a broader temporal horizon also finds expression in the Salish world in a form of thinking that approaches the present in a manner that both looks back three generations, and forward three generations at the same time. It finds expression linguistically in some orders where, for example, the word for great-great-grand-parent, is the same as the word for great-great-grand-child[34]. This orientation to decision-making and responsibilities across time is explicitly captured in the final clause of the WBSA. Immediately above the signature line, it reads, «The Museum and the Artist honour these commitments to each other, to the Witness Blanket and to future generations to come».

In the common law world, one might approach such a clause with caution, thinking about concepts like the rule against perpetuities. Or, one might wonder if this is simply an aspirational statement akin to ‘Til death do us part.’ But again, in the context of a partnership working across two legal orders, one is holding together modes which seek clarity/specifity around both duration and finality, and modes which seek openness to the ways in which the parties can work challenges that may emerge in the context of changing conditions. Support for the kind of philosophical thinking behind this understanding of the temporal horizon appears in the WBSA-Appendix C: Past, Present, Future. Again, what appears there might be understood as a kind of pedagogical intervention, one aimed at articulating a quite different sense of how accountability might implicate responsibilities to not only the present, but also the past and the future

Because such an understanding may require some stretching, note that the duration clause also provides a minimum time horizon for the parties to work towards. Recall that the parties also explicitly agreed to uphold their commitments for a minimum of 10 years. At the 10 year mark, unless the parties mutually agree to end the agreement, it would continue.

And what then of endings? What would be the process through which this agreement to be collaborative stewards might be unravelled? On page 3 of the WBSA, the parties say,

Note here the focus on willingness to work together with others to both explore and come to decisions about the ways in which the unravelling can happen. This is not about seeking an external arbiter or specifying a particular result. Indeed, let us return to the question of money. In the Canadian common law context, failures of contract frequently involve a monetary approach to breach: a defaulting party is often required to ‘pay back’ the other, or to make compensation in the form of a damages award. Here, an ending would not implicate the paying back of fees paid under the WBSA, since a decision to stop jointly stewarding has no impact on the initial decision of both parties to gather funds to put towards a legacy. The focus is not on the rights of the Museum or the Artist, nor on ‘breach’ or failure of responsibilities; the focus remains on the needs of the Witness Blanket to be handled with care and respect. As both Carey Newman and the Museum have noted, once the focus is off the rights of the signatories and is focused on the needs of the Witness Blanket, there is a profound shift in how one thinks about solutions, including solutions that have to do with endings.

To summarize, when one looks at these elements in the written text of the WBSA, one can see a shift in thinking that moves from saying what law “applies”, to asking how two legal orders can work together to “guide” the parties in joint stewardship. Again, law is here invited into an artistic and collaborative practice that is perhaps a better fit for understanding art as something that might function in relationships, and not only as an object to which something can apply. It helps us see law not only as rules or standards, but also as practice, procedures, principles and more.

In this section, we turn to parts of the WBSA that are less familiar to people trained primarily within Western legal orders – specifically, to those parts of the Agreement embedded in legal practice less attached to written texts, than to texts that might be described as ‘arts-based.’ Recall that the WBSA becomes ‘legal and binding’ through the operation of conventions from two legal orders. Within Canadian Common Law, an agreement is reduced to writing, and it becomes legal through the affixing of signatures, appropriately witnessed. And so, as we have seen above, the WBSA does appear in paper form, with all the conventions one would expect (signed, dated, witnessed). Within Kwakwaka’wakw law, certain kinds of agreement were marked through public ceremony, and were recorded in different ways. Indeed, it is precisely such ceremonies that were prohibited under the Potlach Ban discussed earlier.

Fig. 6 – Carey, John and Heather in ceremony; photo credit: Media1

Fig. 6 – Carey, John and Heather in ceremony; photo credit: Media1

Let us turn then to the question of the ceremonial, as part of the realization of lawful commitments under Kwakwaka’wakw law. As one might expect, in a relationally based agreement of this sort, the parties would be committed to learning how to be lawful in both legal traditions. WBSA-Appendix A: Kwakwaka’wakw Ceremony is the starting point. It stands as a kind of pedagogical tool, and as a summary of the elements of Kwakwaka’wakw law and ceremony that are to be drawn into action. Paragraph one of that Appendix is reproduced here:

There are several things to note here. One is the reference to forms of ‘art’ that should be understood as legal: carved poles, bentwood boxes, ceremonial blankets, rattles, talking sticks, songs. The invitation is to understand that oral culture, in this sense, is not about a lack of ‘writing’, but about embedding a legal story in ways that actively draw participants into an embodied engagement with law. Witnesses, for example, are not simply documenting that something was signed, or being called upon to validate truth in a courtroom context. Rather, they are called upon to remember, to tell, and retell a story. Further, because there is always more than one witness called, the recording of memory can be expected to happen in ways that create a richer legal tapestry and make memory something that is continually drawn into the present by an obligation to retell. Memory here is attached to the recording of an event in poles, boxes, blankets, rattles, sticks and songs. Each such object would also invite the storytelling that accompanies the object, and each becomes a pathway to memory (through things that are touched, carried, viewed, heard, smelled, used, and more). One can see in this practice the embedding of legal memory in a very rich proprioceptive field, attentive to the varieties of human abilities to learn or remember through a wider sensorium (one can access and carry legal memory and obligation through neural pathways that connect us more deeply to our neurological capacities).

Fig. 7 – Box of Treasures, Mask, Dancer, Rattle, guests present; photo credit: Media1

Fig. 7 – Box of Treasures, Mask, Dancer, Rattle, guests present; photo credit: Media1

In the next paragraph of the WBSA-Appendix A: Kwakwaka’wakw Ceremony, one learns about the important principle of feasting:

Fig. 8 – Witness Andy Everson reporting back to the gathered guests;

Fig. 8 – Witness Andy Everson reporting back to the gathered guests;

photo credit: Media1

This paragraph then documents what a feast involves for the parties to the agreement. It sets out the protocols, so that a person who is invited to attend will both know what to expect, as well as have a framework to make sense of what they are seeing. It explains the specific context for this kind of witnessing, decentring the Western idea of a witness as primarily rooted in criminal or civil trials practice, where people are being asked to provide evidence of injuries, harms or entitlements. In the WBSA discussion of ceremony, there is an explicit acknowledgment that witnessing is partial and subjective, embedded in the particular experience of specific people. Witnessing is also tied not just to what is seen, or heard, but also to the affect-laden feeling of the experience. Witnesses are asked both to watch what has transpired, and then to share all that with the others at the Ceremony. This means that, for each person present at the Ceremony, they too will have had the experience of seeing, hearing and feeling. Part of that will include the experiencing of being witness to the Witnessing. That is to say, people attending the ceremony/feast as guests are invited to hear four different Witness accounts/reports, with all their differences and affects.

This Witnessing is not directed to ‘proof’ or ‘validation of data’, so much as it is directed to creating pathways of shared experience, and to creating pathways of connection between those who were present at the Ceremony (connections that are multiple, rather than singular, connections that validate the many ways of seeing and processing a shared experience). This paragraph makes explicit that the goals of Ceremonial feasting are linked to practices of governance, both legal and social, directed to sustaining the relationships of trust that will support an agreement to join in collaborative stewardship. The feasting, put another way, seeks to build and maintain the relations that will be necessary to do the work of stewarding.

How then will the parties implement what the Appendix refers to as “cultural teachings”? The Appendix lays out the things that the Museum and Artist have agreed to do together to ‘enact the agreement and maintain the relationship’. Just note here the language of ‘enactment’ and of ‘maintenance’ (which implies both a starting point, a making real, and also ongoing work). They agree:

In these commitments, it is clear what the obligations and procedures are for enacting the agreement in a way that accords with two quite different legal orders. What is also significant is that there is an integration of people into a shared legal experience: both Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants signing contracts in a way that is lawful within Canadian common law; both Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants taking up roles within Kwakwaka’wakw legal ordering. Let us stop here to note that the words “Witness” and “Story Keepers” are also defined terms in the WBSA-Appendix B: Definitions:

Eight people are charged with holding the written text, and another eight people charged with holding an oral record of the context for the agreement. Thus, after Inaugural Ceremony (held in 2019), there were 16 people holding and keeping knowledge of the agreement in both of its legal forms. Half of these people are doing that holding from within their own legal order, and half of them have been invited to do that holding in the context of a legal order that is not their own. One might say we then see something that involves equivalent relations of respect towards the legal traditions of the other, without attempting to collapse them into a singular approach, or focusing on questions of ‘tie-breaking’ in the event of a conflict. There is a new community of knowledge keepers being built together. The term “community” is also defined in the agreement.

Fig. 9 – Community joining to dance with the agreement,

Fig. 9 – Community joining to dance with the agreement,

now held in the box of treasures; photo credit: Media1

One can see here how the Ceremonial portion of the agreement links to the Written portion of the agreement. In each case, there is an acknowledgement that things may shift, people may no longer be able to follow through on their commitments, it may be necessary for change. Rather than setting out what we might think of as “breach” conditions, the agreement sets out a process for resolving those problems by identifying the people who need to be involved. This will include those who have been charged with remembering the text and context. They will be people who have feasted together, shared stories, and built relationships to each other and to the Blanket. This community, over time, will increase to include those present at subsequent gatherings. It will be composed of a group of people who share a ‘longue durée’ understanding of the Witness Blanket and its place in time. This is a quite different way of understanding the obligation of witnesses and story keepers; they remain sutured to the care of the Blanket, with an understanding that the WBSA represents not a point in time, but an ongoing set of relationships and commitments.

Fig. 10 – The feel of ceremony and feasting; photo credit: Media1

Fig. 10 – The feel of ceremony and feasting; photo credit: Media1

On a more personal note, let me circle back to the beginning of this article. In 2019, a group of us from ILRU (the Indigenous Law Research Unit at the University of Victoria,) travelled from Victoria to Comox to attend the inaugural ceremony for the Witness Blanket Stewardship Agreement. We had been invited to attend as guests. Our group included Jessica Asch, Tara Williamson, Brooke Edmonds, and Lindsay Borrows. It was an intergenerational group, as we were also joined by my mother Arta, and by Lindsay’s baby Wasaya. The process of the ceremony and feast followed much of what is set out in the discussion above. But the experience of being in that space of ceremony as a law professor/guest exceeds what can be easily captured in words. I had the deep sensation of entering into a differently structured temporal space, where past, present and future touched up against each other.

Fig. 11 – The Dancers and the Fire; photo credit: Media1

Fig. 11 – The Dancers and the Fire; photo credit: Media1

The felt experience of the event worked on so many levels: I can still draw up the heat and smell and sound of the fire, tended by a firekeeper throughout the event; I can feel the beat of the drums, and the rhythm of the dancers as their feet moved on the bare earth of the floor. In know where I was sitting with respect to the images reproduced above, know who was sitting alongside me, recall the angles from which I experienced the dances, songs and speeches.

There are strong physical sensations attached to the memories of what I heard and saw. I can place myself joining others on the dirt floor at the end, as we danced in shared rhythm around the fire. I can easily draw up the sensation of being overwhelmed by the gifts were given at the end (indeed, in spite of all I knew [intellectually] to expect about potlach ceremonies, I was not prepared for the affective power of receiving those gifts)[36]. And I can pull up the taste of the salmon, and of oolican grease that accompanied the meal. I can hear echoes of conversations around the tables as people sat with each other, processing what we had seen and heard. The echoes of all those experiences continue to resonate in my mind and body.

Fig. 12 – The drums and songs; photo credit: Media1

Fig. 12 – The drums and songs; photo credit: Media1

With the passage of time, I have been struck by the ways the power of this ceremonial experience has had resonance in contexts that seem somewhat distant from the question of residential schools, genocide, and national memory. As just one example, in the context of my work teaching Business Associations, I now find myself seeing the power of ceremony as a way of addressing the challenges of what we might call corporate memory in the context of relationships between people and institutions[37]. With all institutional entities (societies, corporations, governments), one can anticipate changes in decision-making personnel, as people move from one job to another, and as Boards of Directors turnover, as elections draw new people in. Is the review of a written agreement (or contractual terms of reference) enough to help the people who occupy these new roles truly understand the relationships they are part of? My sense is that written agreements are simply not powerful enough to do the necessary work. Can attention to the power of art and the ceremonial provide other avenues? Let us pause for a moment to think about the WBSA. The agreement involved Carey Neman (a human person) and the Museum (an incorporated person), but the negotiations on the part of the Museum were enacted through very specific (human) people. Those people formalized their commitments and responsibilities in the deeply affective laden context of ceremony and feasting. As I write this article, and as the time for the next renewal feast approaches, the Museum has a completely new set of people in the roles of CEO, archivist, and lawyer. In addition to the commitment to the annual review of the written commitments, the WBSA also contains a commitment to holding a renewal feast each 4 years. As a result, there is a built-in mechanism for connecting new people to their obligations through the affect-laden power of ceremony and feasting. It functions something like an aide-mémoire (aid for daily living) for an institutional entity. The feast creates the context for the renewal of relations, through all the work of planning for the feast (which draws in people to the unavoidable work of planning), and for the event itself, which then provides the space for people to sit with each other in a shared space of storytelling, and space of gifting, and a context where food provides the space for people to begin to build relationships to and with each other.

I suppose the point here is to note the deep power in the relationships of law and art. The WBSA models the capacity to pull so many witnesses into engagement, and in the process, nourishes very different kinds of relationships, ones that honour the reality of legal pluralism, and which invite us to inhabit a world in which law and art can be something that we do together. It invites us to inhabit our world of entanglements in ways that let us build relations with people who do law differently and find ways to work together even in the face of those differences. Entanglements worth pursuing.

Abley, Mark (2014), Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, Toronto, Douglas & McIntyre

Bracken, Christopher (1997), The Potlatch Papers: A Colonial Case History, Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Bryce, Peter Henderson (1922), The story of a national crime: being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada; the wards of the nation, our allies in the Revolutionary War, our brothers-in-arms in the Great War, Ottawa, James Hope & Sons, Ltd.

Carlson, Keith (ed.), Albert (Sonny) McHalsie (cultural advisor), Jann Perrier (Graphic Artists and Illustrator) (2001), A Stó:Lo-Coast Salish Historical Atlas, Vancouver, Douglas & McIntyre

Everson, Keisha (2017), Determination: Revitalizing Culture in the K’omoks Valley, in «Kumugwe Cultural Society», https://kumugwe.ca/ bighouse/ (consulted October 3, 2023)

Hamilton, Robert, Joshua Nichols (2019), The Tin Ear of the Court: Ktunaxa Nation and the Foundation of the Duty to Consult, in «Alberta Law Review», 56.3, pp. 729-760

Hudson, Kirstie, Carey Newman (2019), Picking up the Pieces: Residential School Memories and the Making of the Witness Blanket, Victoria BC, Orca

Johnson, Arta (October 27, 2019a), The Witness Blanket Ceremony, in «Larch Haven», https://larchhaven.blogspot.com/2019/10/the-witness-blanket-ceremony.html (consulted July 28, 2023)

Johnson, Arta (October 28, 2019b), Feasting and Gifting, in «Larch Haven», https://larchhaven.blogspot.com/2019/10/gifting-and-feast.html (consulted July 28, 2023)

Johnson, Rebecca (2015), Taking the Call: An Introduction to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission and Its 94 Calls to Action, in «Canadian Yearbook of Human Rights», 1, pp. 29-37

Johnson, Rebecca (January 31, 2020), Implementing Indigenous Law in Agreements – Learning from ‘An Agreement Concerning the Stewardship of the Witness Blanket’, in Reconciliation Syllabus: a TRC-Inspired Gathering of Materials for Teaching Law, https://reconciliationsyllabus.wordpress.com/2020/01/31/implementing-indigenous-law-in-agreements-learning-from-an-agreement-concerning-the-stewardship-of-the-witness-blanket/ (consulted July 28, 2023)

Johnson, Rebecca (2024, forthcoming), Testify! Reflections on Cultural Legal Studies and Indigenous Legal Orders, in Crawley, Karen, Thomas Giddens, Timothy D. Peters (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Legal Studies, New York, Routledge

Johnson, Rebecca, Bonnie Leonard (2020), Coyote and the Cannibal Boy: Secwépemc Insights on the Corporation, in Fitzgerald, Oonagh (ed.), Corporate Citizen: New Perspectives on the Globalized Rule of Law, Waterloo, Center for International Governance Innovation, pp. 31-46

Kolsut, Julian (2018), Indigenous Law art exhibit on display in Victoria, «CHEK News», 30 September, https://www.cheknews.ca/indigenous-law-art-exhibit-on-display-in-victoria-494409/ (consulted August 3, 2023)

Mahoney, Kathleen (2016), Canada’s Origin Story, in Big Thinking (Lectures organized by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences), May 10, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aaw5_8UuiBM (consulted July 28, 2023)

Moran, Ry (2022a), Episode 2: A Box of Treasures, in Taapwaywin: talking about what we know and what we believe (A UVic Libraries Podcast), https://www.taapwaywin.ca/post/episode-2-a-box-of-treasures

Moran, Ry (2022b), Episode 3: Preservation, Destruction, Transformation, in Taapwaywin: talking about what we know and what we believe (A UVic Libraries Podcast), https://www.taapwaywin.ca/post/episode-3-preservation-destruction-transformation

Mosby, Ian (2014), Food Will Win the War: The Politics, Culture and Science of Food on Canada’s Home Front, Vancouver, UBC Press

Napoleon, Val (2009), Ayook: Gitksan Legal Order, Law, and Legal Theory, PhD Dissertation, University of Victoria Faculty of Law

Napoleon, Val (2010), Living Together: Gitksan Legal Reasoning as a Foundation for Consent, in Webber, Jeremy, Colin M. MacLeod (eds.), Between Consenting Peoples: Political Community and the Meaning of Consent, Vancouver, UBC Press, pp. 45-76

Napoleon, Val, Rebecca Johnson, Debra McKenzie, Richard Overstall (eds.) (2024, forthcoming), An Interrupted Intergenerational Conversation: Indigenous Art and Societal/Cultural Expressions, Toronto, University of Toronto Press

Pinder, Leslie Hall, (1999), The Carriers of No, in «Index on Censorship», 4, pp. 65-74

Robinson, Dylan (2020), Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press

Sniderman, Andrew Stobo, Douglas Sanderson (2022), Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation, New York, HarperCollins Publishers

Turner, Nancy J. (1998), Plant Technology of First Peoples in British Columbia, Vancouver, UBC Press

Welsh, Christine, Sylvia Olsen (2003), Listen with the Ear to Your Heart: A Conversation About Story, Voice, and Bearing Witness, in Norris Nicholson, Heather (ed.), Screening Culture: Constructing Image and Identity, Lanham-Boulder-New York-Oxford, Lexington Books, pp. 143-156

Wickwire, Wendy (2019), At the Bridge: James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging, Vancouver, UBC Press

The mandate of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights (the “Museum”) is to explore the subject of human rights, to enhance the public’s understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others, and to encourage reflection and dialogue. The Museum is located on ancestral lands in Treaty 1 Territory, that have always been and continue to be home to Indigenous peoples.

The Witness Blanket, a large-scale art installation, was created by Carey Newman (the “Artist”) as a national monument to recognize the atrocities of the Indian Residential School era, honour the children, and symbolize ongoing reconciliation.

As a national museum dedicated to the evolution, celebration and future of human rights, the Museum understands and embraces its responsibility to respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action to redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of reconciliation in Canada.

In recognition of its responsibilities towards reconciliation, and the importance of the Stories about and held within the items that make up the Witness Blanket, the Museum respectfully wishes to enter into an agreement with the Artist to become joint stewards of the Witness Blanket.

This agreement forms part of a complex understanding that is only fully realized through both the signing of the written agreement and the performance of, and joint participation in, ceremony observed, understood and remembered by Witnesses. Together, the written and oral commitments form the foundation of this ongoing relationship based on mutual trust and respect.

Together, the Museum and the Artist acknowledge and agree to the following principles:

We acknowledge the cultural and spiritual significance of the Witness Blanket, as well as the profound knowledge and experiences embedded in the Witness Blanket.

We recognize the importance of the Witness Blanket not only for its representation of Canada’s human rights history and the genocide committed by Canada against the Original peoples of the land we share as our home, but also for the opportunity it offers to advance dialogue and discussion about genocide and reconciliation in Canada.

We respect the Stories and People whose stories are attached to the Witness Blanket and commit ourselves to uphold and honour the cultural integrity of the Stories and the People they represent.

We recognize that the Witness Blanket is not owned by any single person, and that this agreement and any exchange of funds does not transfer legal ownership of the Witness Blanket, but formally shares responsibility for the physical and spiritual care of the Witness Blanket.

We agree that any rights associated with this agreement reside with the Witness Blanket, and accept that as collaborative stewards, the Museum and the Artist share the responsibility of making decisions that are in the best interest of the Witness Blanket.

We agree to act in partnership and in accordance with traditional teachings that include Respect, Humility, Love, Truth, Honesty, Courage and Wisdom, and the concept of Past, Present and Future.

The spirit and intention of this agreement is to ensure that the Stories told by the Witness Blanket are preserved and shared for future generations.

Honouring the past, respecting the present and acknowledging our responsibility to the future, the Museum and the Artist agree to transfer physical custody of the Witness Blanket into the Museum’s care and stewardship.

The responsibilities and commitments made under this agreement are as follows:

- The Museum will provide respectful lodging for the Witness Blanket and commits to caring for the Witness Blanket for the duration of this agreement.

- The Museum understands and honours the responsibilities and duties required to be respectful stewards of the Witness Blanket.

- The Museum will provide recommendations for the conservation of the Witness Blanket and will work in collaboration with the Artist to determine the most respectful methods for treating and preserving the Witness Blanket.

- The Museum will work with the Artist to identify an appropriate selection of Stories to transfer with the Witness Blanket to support the repair, display and sharing of the Witness Blanket.

- In discussion with the Artist and the Community, the Museum will make reasonable efforts to provide access to the Witness Blanket in a variety of ways and formats.

- The Museum and the Artist will collaborate in the development of a reproduction of the Witness Blanket for the purpose of creating a travelling exhibition, enabling wider access to the Witness Blanket Stories while preserving the original Witness Blanket for future generations. The Museum will assume responsibility for the management of the travelling exhibition.

- The Artist will provide guidance with respect to the cultural protocols, care, maintenance and preservation of the Witness Blanket and will support the Museum in its commitment to care for it.

- The Artist will be responsible for responding directly to requests for personal appearances.

- The Artist and the Museum will work together to designate the future voices that will represent the Museum, the Witness Blanket and the Artist’s family in order to continue the collective conversation and fulfill our respective responsibilities to this agreement while honouring the Newman family’s inherent connection to the Witness Blanket.

- This agreement honours the terms of the financial arrangement noted in Appendix D.

- This agreement will be guided by both Kwakwaka’wakw traditional legal orders and Canadian Common Law.

In fulfilment of our commitment to this ongoing relationship, the Museum and the Artist will review this agreement yearly (meeting remotely or in person as appropriate) in addition to committing to a renewal feast every four years on or around the anniversary of the inaugural feast. Through these points of connection, this agreement may evolve or be revised by mutual agreement in writing.

In the spirit of this partnership, it is intended that this agreement will endure for seven generations forward. The Museum and the Artist agree that they will uphold their commitments and this agreement for a minimum of ten (10) years, following which the agreement will continue unless both the Museum and the Artist (or Artist’s designate) agree to end the agreement.

The Museum and the Artist will willingly enter into discussion with the Community (that includes Story Keepers and Witnesses) regarding respectful handling of the Witness Blanket should this agreement come to an end.

The Museum and the Artist honour these commitments to each other, to the Witness Blanket, and to future generations to come.

Our signatures below acknowledge our commitment to this relationship of trust and our responsibilities therein.

John Young Carey Newman

President and CEO Artist

Canadian Museum for Human Rights The Witness Blanket

Dated this ________________th day of ___________________, 2019.

Oral culture has governed Kwakwaka’wakw social and legal orders since time immemorial. Cultural, social and legal transactions, agreements and the sharing or transmission of rights were marked through ceremony and recorded in several ways. One was by calling Witnesses who were paid to remember, tell and retell the story of the events that had transpired. Another was through the creation of artistic records that could take many forms, from the raising of a monumental carved pole, to the design on a bentwood box or ceremonial blanket, to a small rattle, a talking stick or even a song. Connected by their dynamic and continuous use, these methods were very effective at preserving our histories from generation to generation, through millennia.

Another important principle in Kwakwaka’wakw ceremony is feasting. The art of hosting (feasting) includes a cultural practice of invitation, seating guests, blessing the space, identifying Witnesses, feeding guests, singing a feast song, storytelling and gift-giving. As a finale, the Witnesses are invited to speak. They recount what they saw, what they heard and how this made them feel. This, their story, our story, is what they carry and will retell to others. These feasts or potlatches remain an important aspect of Kwakwaka’wakw governance and social and legal orders, and centre around building and maintaining relationships based in trust, recognition, mutual respect and friendship.

In recognition of these cultural teachings, and to enact this agreement and maintain the relationship, the Museum and the Artist agree on the following:

- To come together in ceremony on the traditional territory of the Kwakwaka’wakw people within one year of signing the paper document.

- To create a physical embodiment of the agreement in the form of a feast dish or box of treasures. This piece will both symbolically and literally hold the story of this agreement.

- To mutually agree upon and name four Story Keepers who will each receive copies of the written document. The Story Keepers will be tasked with telling and retelling the story of how the document was created and remembering the original spirit and intent of the agreement.

- To name, call and recognize four Witnesses who will be asked to speak at the conclusion of the ceremony, and then remember and recount the event for future generations.

- To feast together as a demonstration of their mutual respect and friendship, and their commitment to honouring the Witness Blanket.

- To maintain and renew the relationship over time, coming together to share in food and remembrance at least once every four years, but as often as is required to fulfill their commitment to the care and stewardship of the Witness Blanket.

In this way, we intend to bring together Indigenous and Western legal principles in a manner of mutual respect, where each supports and upholds the other.

NB: Throughout the written agreement, certain words – that would not usually be capitalized in standard English grammar – have been capitalized to signify their importance in the context of the Witness Blanket. They are defined below for additional understanding, along with other significant non-capitalized words.

Community means the group that represents the interests of the Museum, the Artist and the Witness Blanket. The Community would be called upon if significant changes were to be made to the agreement, or if either party could no longer fulfill their commitments to the agreement. This group includes the Story Keepers and Witnesses identified through the traditional ceremony and oral component of this agreement.

lodging means a culturally appropriate place to store and care for the Witness Blanket, recognizing that the Witness Blanket includes pieces that are treated as living beings. A lodge is considered a place of rest and may incorporate protocols indicated by Elders. It can be an alternative to the use of terms used in a museum context for storage, display or preservation of objects (e.g. display case, vault).

People means the persons whose lives were impacted by Indian residential schools – students, mothers, fathers, survivors and their families. It includes persons from the past, the present and the future.

seven generations is a cultural phrase that indicates forward thinking and future sustainability, roughly translated into 140 years.

spiritual care means acknowledgement of cultural protocols that are required to respectfully care for the Witness Blanket in harmony with Western concepts of conservation and preservation.

steward/stewardship means holistic responsibility for the care of the Witness Blanket, acknowledging the agency and rights of the Witness Blanket, and recognizing that no one person owns the Witness Blanket. Stewardship has been purposefully chosen in lieu of acquisition.

Stories means the physical items and recorded oral testimony that contribute to the whole of the Witness Blanket. Stories is capitalized to recognize that these items are living beings embodied in the Witness Blanket.

Story Keepers means the people designated by the Artist and the Museum (four from each side) to receive copies of the written document. Designation of Story Keepers, detailed roles and succession plans are articulated in Museum procedures accompanying this agreement.

traditional teachings refer to traditional concepts or lessons understood to be sacred and which form the foundation for healthy, respectful relationships. The traditional teachings listed in this agreement are not universal but are mutually shared by the Kwakwak’awakw and Coast Salish traditions of the Artist, and traditions of Treaty 1 Territory nations where the Museum resides.

Witnesses means the people designated by the Artist and the Museum (four from each side) to observe, understand and remember the specific context of the agreement. Each Witness holds an oral record of the agreement. Designation of Witnesses, detailed roles and succession plans are articulated in Museum procedures accompanying this agreement.

The cultural values of respecting the past, honouring the present and responsibility to the future ask us to consider our own existence within the continuum of life. The lives we live are built on the wisdom of our ancestors who came before us. They entrusted us with stewardship of the land that sustains us, the air we breathe, and the water that gives life to all. When we acknowledge this, we take on the responsibility of continuing their ways and decisions. We do this by respecting and carrying their wisdom forward, passing on the same gifts to future generations that were given to us.

During our lifetime, although we have access to the resources and knowledge that surround us, they do not belong exclusively to us, they also belong to those who came before us and the generations yet to come. The generation of the present must always consider that the decisions we make and the actions we take reflect our past and impact the future. In this way we are connected across time and it requires us to embody each of these principles in the way that we walk. This is our system of accountability.

Both the Artist and the Museum recognize that the terms of this financial arrangement do not accurately reflect the true value of the Witness Blanket, as its value is both immeasurable and cannot be monetized.

It also recognizes that, due to budgetary limitations and public accountability, the Museum must be prudent in establishing its financial commitments.

As such, the Museum will pay an initial one-time fee of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars ($250,000) to the Artist in consideration of the opportunities which this collaborative stewardship represents for the Museum.

In addition, the Museum also commits to applying best efforts to raise up to an additional five hundred thousand dollars ($500,000) through fundraising and/or sponsorship to further support the project which will be transferred to the Artist in further consideration of the value placed on the Witness Blanket and the opportunities that it represents. However, if despite best efforts, no additional funds are raised, then the CMHR will not be required to transfer any additional payments to the Artist beyond the initial one-time fee of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars ($250,000).

To uphold the principles, spirit and intent of this agreement, and to honour residential school survivors and the commitment they made to reconciliation through the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Commemoration Initiative, which was the original source of funding for the creation of the Witness Blanket, the Artist agrees to commit the entirety of the fee resulting from this financial agreement toward the establishment of a legacy project that will continue the work of art and reconciliation.

[1] For some background on the Bighouse, see Everson (2017).

[2] Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996, 5 vols).

[3] Mahoney (2016).

[4] Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015, 6 vols).

[5] For two books that detail these histories in a rich and compelling narrative form, see Wickwire (2019) and Sniderman/Sanderson (2022).

[6] In making attendance mandatory, and thus authorizing the removal of children from their families, Scott said: «I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone [...] Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill»: National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, vol. 7, 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3).

[7] These words, though spoken first by an American military officer, are often attributed to Duncan Campbell Scott. For more on a man now largely understood as a villain in Canadian history, see Abley (2014).

[8] Bryce (1922) and Mosby (2014), documenting patterns of neglect and malnutrition of children in these schools, as well as the use of children in human biomedical experiments without their consent.

[9] See Sniderman/Sanderson (2022), p. 37.

[10] This history is explored in more detail in Johnson (2015), pp. 29-37. Note that the IRSSA $1.9 billion dollar settlement has been recently surpassed by a $40 billion dollar settlement in another class action brought on behalf of Indigenous children against the state, the First Nations Care Society settlement of 2023: https://www.fnchildcompensation.ca/.

[11] 1. Common Experience Payment ($1.9 billion) was based simply on number of years one was in residential school [$10,000 for first year, and $3,000 for each subsequent year]; 2. The Independent Assessment Process ($1.7 billion) was a separate process set up to resolve particular claims of sexual abuse and serious physical and psychological abuse; 3. Health & Healing Services ($125 million) were to enable elders and aboriginal community health workers to support former students in terms of mental and emotional health. The Settlement Agreement itself is available online: http://www.residentialschoolsettlement.ca/IRS%20Settlement%20Agreement-%20ENGLISH.pdf

[12] Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015, 6 vols).

[13] The 1895 amendments to the Indian Act said: «Every Indian or other person who engages in, or assists in celebrating or encourages either directly or indirectly another to celebrate, any Indian festival, dance or other ceremony of which the giving away or paying or giving back of money, goods or articles of any sort forms a part, or is a feature, whether such gift of money, goods or articles takes place before, at, or after the celebration of the same» [is guilty of an offence and liable to imprisonment of a term not exceeding 6 months and not less than 2 months]. As Bracken (1997), p. 119 notes, the Ban prohibited every possible circulation of money, goods or articles between Indigenous people where done within the cultural structures of Indigenous legality.

[14] U’mista Cultural Centre, History of the Potlach Collection, https://www.umista.ca/ pages/collection-history (consulted October 2, 2023).

[15] Napoleon (2010) p. 47. This article provides an extended exploration of feasting/potlaching as an aspect of Indigenous (Gitksan) public law and legal reasoning.

[16] Napoleon/Johnson/McKenzie/Overstall (2024, forthcoming).

[17] Delgamuukw v. BC (8 March 1991) Smithers No 0843 (BCSC). For more on Gitxsan law, see Napoleon (2009). The trial decision in Delgamuukw was overturned by the Supreme Court in 1997; the case set new precedent for Indigenous rights and affirmed the use of oral testimony in Canadian courts.

[18] For a powerful narrative response to Justice McEachern, written by one of the lawyers in the case, see Pinder (1999). As an example of the ways that Justice McEachern’s failure has entered into legal discourse, see also Hamilton/Nichols (2019).

[19] For more on the relationships of Indigenous Laws and the Arts in the Testify Collective, see Kolsut (2018) and Johnson (2024, forthcoming).

[20] To return to an example with the Gitxsan and poles, Napoleon (2010), pp. 46-47 affirms the point about the legal significance of such monumental carvings: «The significance of the poles is that they are carrier[s] of social, spiritual, territorial, and economic rights and privileges. On them are carved the crests (sing. ayuks) representing the specific privileges drawn from the ancient, formal, collective oral histories (adaawk), which are essential cultural property owned by the kinship groups».

[21] On the challenges of national memory, see Moran (2022b). This podcast episode deals with difficult histories in Canada, Germany and the UK, asks, «How do we remember injustices when the physical signs of that history are no longer visible? What do we do with the buildings and structures that still stand? And how are the memories embedded within these sites both painful scars and opportunities for healing?».

[22] Images and stories are accessible on the Witness Blanket’s website: https://witnessblanket.ca/about-the-blanket.

[23] For an account of the making of the Witness Blanket, see Hudson/Newman (2019).

[24] During the time the Blanket was being constructed, his sisters grew their hair long. It was then cut off in ceremony, acknowledging the generations of indigenous children whose hair was cut off upon their arrival at school. See Hudson/Newman (2019), pp. 134-139.

[25] Turner (1998). See also Alice Huang, Cedar https://indigenousfoundations.arts. ubc.ca/cedar/.

[26] See Hudson/Newman (2010), p. 7.

[27] On practices of witnessing in West Coast Indigenous legal cultures, see Welsh/Olsen (2003).

[28] Carey Newman shared these observations with the first year law students at the University of Victoria, March 7, 2023.